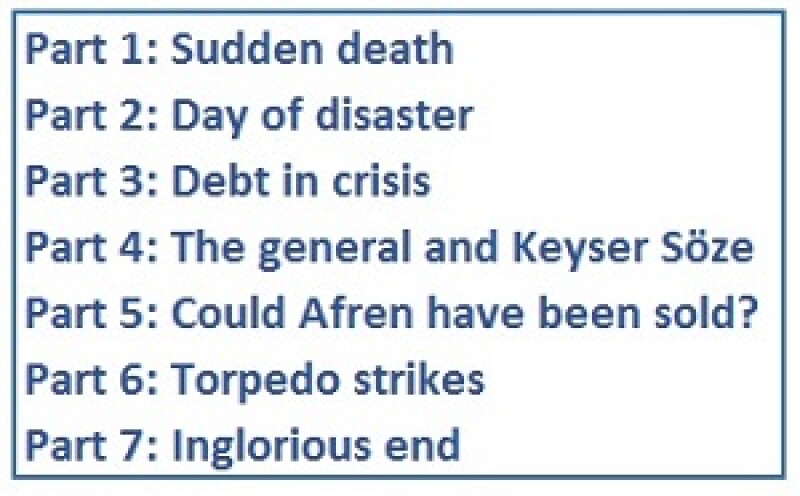

[Part 1: Sudden death] | [Back to main page]

But the company stayed in business. Many hoped it would recover and thrive once more.

On July 31, 2015, Afren shattered that hope. It declared that, having explored all possible routes, it could no longer avoid administration. Business advisory firm AlixPartners took control of the company as administrator.

This followed the revelation on July 15 that, after an operational review, Afren expected materially lower “near term” production from its assets than previously envisaged.

This bland wording — no details have been given yet of how low production would fall — had a devastating meaning. Throughout the past turbulent year of scandal, a steep fall in the oil price and a debt restructuring, shareholders and bondholders had believed Afren basically still had a viable business, with some oilfield operations that were producing oil and would continue to. Now, even that was cast into doubt.

After July 15, Afren negotiated desperately with its lending banks and bondholders to secure some quick funding to fill its short term liquidity gap and enable it to pay its debts as they fell due.

But those negotiations were bound to fail, one creditor told GlobalCapital early last week. The timeframe was too short, and the amount Afren requested too high.

The demands for money were all the more unreasonable, he added, as they came so soon after an agreement on April 30, when creditors injected $200m of new funding into the firm, with the promise of more.

Suddenly, creditors were being asked potentially to double the funding they had agreed to provide only three months earlier. That April restructuring agreement had been hard enough to secure and took weeks of bargaining between Afren’s creditors.

Afren’s request for hundreds of millions more dollars, the creditor said, was out of the question. Afren was toast.

High hopes, ugly payments

Founded in 2004, Afren floated the following year on Aim, London’s junior stock market, with an initial market capitalisation of £26m, before rising to the main market and eventually entering the FTSE 250 index.

The firm, focused on African oil and gas exploration and production, looked set to make the most of the continent’s growing energy opportunities. At its height, in early 2014, Afren had a share price of £1.69 and a valuation of £1.86bn. On July 31, when it folded, it had dropped below where it started a decade before: worth just £20m, at 2p a share.

Afren’s woes first came to public attention on July 31 2014, when Afren released preliminary results of an investigation by US law firm Willkie Farr & Gallagher. The inquiry, commissioned by Afren’s board, was originally intended to clarify whether Afren needed to disclose to the market certain transactions it had undertaken in 2012 and 2013, but grew broader in scope when Willkie discovered evidence of further malpractice at the firm.

The preliminary results identified the receipt of unauthorised payments “potentially for the benefit of the CEO and COO”. Afren suspended both men, and its share price fell 26%, to £1.10.

The scandal broke at a particularly bad moment for Afren, as it had been about to complete a refinancing of its bank loans and its 2016 bond, which would have given it fresh cash and pushed out its debt maturities.

By October, when Willkie completed its review, the law firm had become certain of its claims. Osman Shahenshah, Afren’s CEO, and Shahid Ullah, its COO, had received $17m of unauthorised payments from some of Afren’s joint venture partners, in exchange for favours, including loans from Afren.

They were dismissed. Other managers, too, had benefited from undue payments and were fired, Afren said.

Management was reorganised. Egbert Imomoh, formerly non-executive chairman, became executive chairman. Toby Hayward, a non-executive director, became interim CEO as Afren searched for a new head.

Some shareholders were concerned the new heads lacked the executive experience to lead a complex oil explorer and producer with activities in 11 countries, let alone a company in crisis. Hayward had been chief executive of Sirius Petroleum for 10 months, but most of his career was as a corporate finance banker.

Fresh bad news

Under the new management, Afren’s share price kept falling, though more slowly. Its three senior secured high yield bonds — $253m due in 2016, $250m due 2019, and $360m due 2020 — followed a similar path.

Issued between 2011 and November 2013, with ratings as high as B/B+ by Standard & Poor’s and Fitch, they had traded above par before the corruption scandal. By late January 2015 they were quoted below 50 cents on the dollar.

The debt and equity falls were worsened by the unexpected collapse in the price of crude oil, which halved between August 2014 and January, to $50 a barrel.

But much of Afren’s woes were specific to the company. In December 2014 it sold its oil price hedges, even as the oil price was collapsing. Afren did not inform shareholders of this until March 2015, enraging some, who said shareholders were given the false impression that Afren was still protected against falling prices.

One investor said the main problem was not that Afren had sold its hedges, but the lack of disclosure, and also that Afren should have hedged a greater part of its production in the first place.

A source close to Afren said there was no legal requirement to disclose the sale any earlier, and that by the time Afren sold its hedges, the price of crude had already dropped significantly, meaning Afren was able to sell them for a good price, and use the cash benefit — $80m, Afren said — to shore up its weakening financial position. “We’re criticised if we sell, we’re criticised if we don’t,” said the Afren source.

Perhaps more importantly, on January 12, 2015, Afren released a damning review of one of its main assets, the Barda Rash oil field in Iraqi Kurdistan, in which it holds a 60% working interest.

The review said Afren’s previous estimate that the field held 190m barrels of proven and probable oil reserves was essentially reduced to nothing. At the same time, “2C”, or best case, resource estimates were cut from 1.243bn barrels to 250m. There was no longer any certainty that Barda Rash held any oil at all: it had become virtually worthless.

Largely because of the Barda Rash write-off, Afren reported on March 13 this year post-tax impairment charges of $2bn for 2014.

[Part 3: Debt in crisis] | [Back to main page]

.

Unless otherwise stated in this article, none of the individuals and institutions mentioned agreed to comment on the record.