When two chief executives leave one of the world’s largest banks, only a month after a management reshuffle meant to consolidate their grip on the strategic transformation of the bank for the next five years, it looks a little careless.

Whether the explanation eventually turns out to be boardroom power struggle, shareholder revolt, regulatory pressure or an unholy combination of all three, the defenestration of Anshu Jain shocked the Street.

Deutsche has had its share of troubles, and Jain’s exit was an opportunity to confirm any number of pet theories.

Maybe Deutsche was too German, maybe not German enough, or caught in the middle. Perhaps the co-CEO model didn’t work, perhaps it never knew what its core business was, perhaps its core business was highly leveraged bond trading. It should have given up on retail banking, or investment banking, or focused on wealth management. Maybe Deutsche should have been more like Goldman Sachs. It shouldn’t have hosed its shareholders with two post-crisis rights issues. Maybe it only stayed afloat because it was rigging Libor, or because it sent its Greek exposure into the public sector at an opportune time. All these theories have been doing the rounds.

Whatever. If there was a way to go long Deutsche Bank opinion pieces, it might have been a decent hedge for the bank’s persistently lacklustre share price.

But what if market observers, and especially business journalists, place far, far too much emphasis on the capacity of a single man, or a pair of men, to transform a business with a balance sheet larger than most countries’ GDP, employing the population of a small city?

Chief executives themselves and the boards which hire them have vested interests in promoting their credentials. Shareholders and journalists alike love a simple — and personal — story.

The narrative goes like this. Anshu Jain has a background as a trader, therefore he must think like a trader, favour trading businesses, and push trader-like approaches to timing the market (with monster rights issues).

By the same token, new CEO John Cryan is an old school corporate financier, so the juggernaut of Deutsche Bank will doubtless turn on a sixpence and become an advice house, offering the mix of balance sheet light, trusted consigliere FIG business that Cryan’s old shop, UBS, is known to be.

But this sort of armchair management is too simplistic for any industry, and far too simplistic for investment banking.

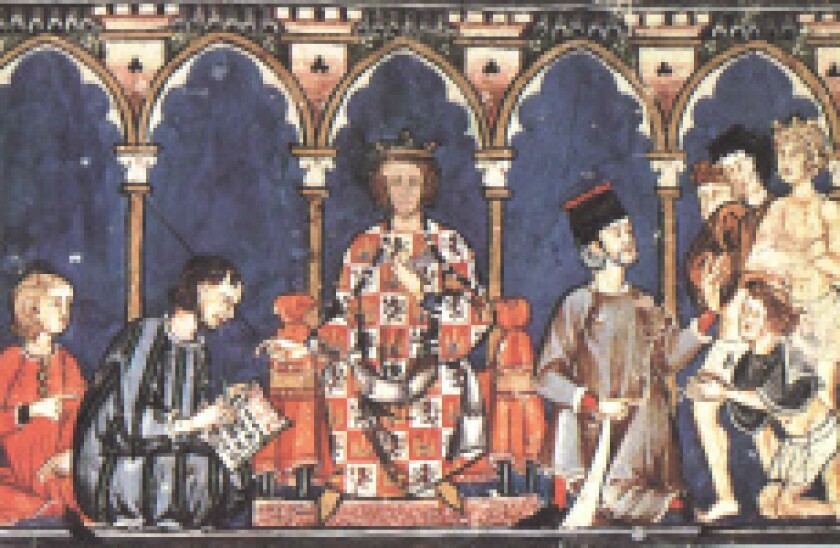

The political model for investment bank management is not a dictatorship, but medieval feudalism.

Warlord's domain

It is a collective of business fiefdoms, connected by loose allegiances and a common balance sheet, run day to day by powerful warlords who run the different business lines. Their loyalty is frequently in doubt. They bend the knee in public, while jockeying for preferment behind the scenes, backed up by legions of mercenaries.

Rulers rule as sovereigns in theory, but depend on the loyalty of their nobles, while political assassination is a frequent hazard.

Because the relationships and networks of individual bankers and salespeople are the major drivers of revenue and competitive advantage, it is hard to imagine it working any other way.

Deutsche, among all banks, used to be seen as embodying this tradition, with an extraordinary level of internal, as well as external, competition for clients and revenue credits.

Today, all banks insist this is over — everyone has horizontal client sharing, holistic product agnostic approaches, enhanced client-centric co-operation and transversal revenue sharing. But it’s hard to believe it has totally disappeared.

Practices like having separate teams with separate reporting lines in the same bank, but pitching against each other, have probably been wiped out, but behind every dreary statement about a strategic reorganisation to serve clients better is a chunk of politics.

The point is, no CEO is as important as they are made out to be. The chief executive is a public face, a fall guy, a figurehead, and a distraction.

Deutsche’s flaws will remain just that under Cryan. If there are cultural issues, then by their nature they will be deep-seated and hard to move. But equally, Deutsche’s army of top banking talent remains in place, and will carry on originating, structuring and placing deals.

When market volumes (which no CEO can control) match up to Deutsche’s business model and franchise (which takes years, if not decades to control), the bank will make a ton of money. When that doesn’t happen, or when regulators change the profitability equation for previously attractive businesses, it won’t.

Leaders, and their exits, make great drama, but just like everyone else, they are prisoners of circumstance.