When the coronavirus pandemic began in March, every CFO in Europe seemed to have the same thought — get liquidity, now. As 2021 begins, their thoughts will be much more diverse.

For some, the pandemic will have been a bruising experience, leaving their balance sheets bloated with debt and creaking at the seams. Others may have more gross debt than before, but are swimming in cash and need to find uses for it.

In many industries, capital expenditure has been reduced to the absolute minimum. How and where it revives will be a big determinant of borrowing needs in 2021.

The overarching theme, however, will be tidying up the crisis funding so many slapped on in 2020.

Anheuser-Busch InBev, the world’s largest brewer, drew down its entire $9bn revolving credit facility less than two weeks after the pandemic hit Europe, setting the tone for corporate financing markets.

Days later, Air France KLM drew all its €1.765bn facility, while Airbus negotiated a new €15bn credit line, in case capital markets shut down.

Moves like these have been replicated up and down the spectrum. Loans bankers were exceptionally busy until June, signing tens of billions of euros of bridge and crisis loans.

Many were quickly refinanced in the bond market, or even prefinanced — the companies raised bond funding before needing to draw the facilities. Some issuers visited new markets to find extra wells of liquidity. Japanese car maker Nissan Motor issued its first euro bonds in September, raising €2bn. The dollar corporate bond market broke all issuance records.

The dash for cash has left many companies carrying high debt at a time when earnings have withered, leading to some wild leverage ratios.

AB InBev’s leverage, for example, hit nosebleed levels over the summer. Analysts predicted it would end 2020 at around 5.8 times Ebitda. The rule of thumb on leverage for companies with its BBB+ rating is two times.

However, fixed income investors are getting used to it. “Investors are becoming a bit more sanguine on the debt reduction capability of corporates,” says Shanawaz Bhimji, senior fixed income strategist at ABN Amro in Amsterdam. “Net debt to Ebitda sits at elevated levels, but quarter three earnings have been quite resilient and there has been a strong beat to expectations in revenue, which tells us that the external environment has become more constructive and that earnings momentum has room to improve further, especially in sectors which do not suffer from renewed lockdowns, such as manufacturing and materials.”

November’s encouraging news that vaccine candidates had succeeded in clinical trials has also helped investors relax about corporate debt piles.

“Net debt to Ebitda has a chance of coming back to pre-Covid levels as early as quarter one or quarter two, 2021,” Bhimji says. This is partly because many businesses have keen incentives to reduce gearing.

“If companies are frowned upon to release dividends again because of high debt levels,” says Bhimji, “the first thing a company is going to do is cut debt to allow a sustainable shareholder distribution, which is what equity investors prefer.”

Firms that cut dividends because of the pandemic span a wide variety of industries, from Intercontinental Hotels Group to Glencore, the commodity trader, and telecoms firm BT.

Decoupling from reality

While companies whose leverage has soared will strive to bring it down, swathes of firms are also turning to the bond market to term out debt. This task has been eased by the European Central Bank’s Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP) and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which have relentlessly pushed down on spreads since the wides of March.

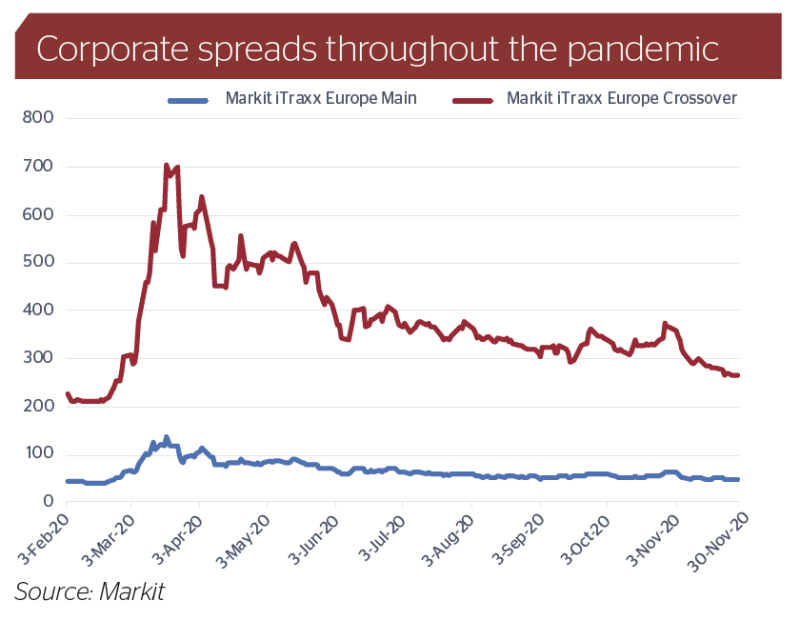

From November 24 for the rest of that month, the Markit iTraxx Europe Main index of credit default swaps was printing at 49bp, the tightest it had been since February and barely a third of the March wides. The higher risk Crossover index was also close to pre-pandemic levels at the end of November, at 268bp.

Many European companies have returned to the bond market multiple times since March — more than in a normal year — benefiting from tighter spreads each time.

“You’ve got an underlying force at work and the markets are very distorted as a result,” says Marco Baldini, head of European bond syndicate at Barclays in London.

Since November 2019, the ECB has bought €5.5bn of corporate bonds a month, a similar pace to the first phase of CSPP, from June 2016 to December 2018. In a special pandemic response, it bought another €21bn, but that had dwindled almost to nothing by October.

This is a double-edged sword for the market. It has provided ample liquidity, ensuring markets remained open during the crisis. But it is also separating financial markets from economic reality.

“It’s not you versus fundamentals, you’re in the market against the ECB or the Fed,” says Baldini. “We are at the mercy of quantitative easing. I don’t know how they will behave going forward, but it seems they’ve got continuing appetite to buy corporate bonds.”

The vacuum sucking bonds out of the market is so strong that it is inflating even assets the ECB will not touch. Hybrid capital bonds, for example, are not eligible for the CSPP, but have rallied, as yield-hungry investors try to juice up their returns. The spread between subordinated and senior debt has thundered in from around 700bp in May to roughly 170bp as December began.

Central bank corporate bond buying “will continue to grind spreads tighter — it doesn’t matter if you qualify for CSPP or not,” says Baldini.

The hybrid rally has stimulated a surge of issues, as borrowers look for liquidity that will not drag on credit ratings. BP printed its first ever hybrid in June, raising a remarkable $12bn in dollars, euros and sterling.

“In the past, hybrid issuance was more a defensive measure to insulate your balance sheet from future shocks,” says Cyril Fleck-Chatelain, head of capital markets solutions at MUFG in Paris. “It’s a different story this time around, as the shock is out there. Hybrids are coming after the crisis as an offensive tool, rather than defensive.”

This marks a “shift in the way people approach hybrids”, he says, “with issuers more comfortable with the asset class”.

The resumption of capex will be an important leading indicator for debt issuance. Troubled firms that need to delever will prioritise that. If the rollout of vaccines has encouraging results, firms in better shape will be keen to invest, either in organic growth or acquisitions. Some, though, will use up their idle cash piles before needing to borrow afresh.

Nonetheless, debt capital markets bankers are characteristically eager to guide companies back to the bond market. “If you’re a company that doesn’t need money but you can fund at these extremely low levels,” says Baldini, “it feels like you should be finding a way to justify taking in some of the funding on offer, maybe via some sort of liability management exercise.”

This practice has become very common in the US, outstripping Europe, where treasurers from Germany to Italy are reluctant to splurge on new debt to fund liability management.

Nonetheless, some companies have completed significant buybacks. Again, BP is a notable example. In September, it executed Europe’s largest ever corporate bond buyback, purchasing $4bn-equivalent using proceeds from the hybrid issue.

Green incentive

There is a clear way for to secure the cheapest debt possible from Europe’s bond market — attach a green label to something CSPP-eligible.

Green bonds have been obliterating new issue concessions for months. German car company Daimler and Finnish paper firm Stora Enso, for example, printed green bonds 20bp and 25bp inside fair value, respectively, in the back end of 2020.

The colossal presence of the ECB’s asset purchase programmes could shape environmental, social and governance investing in new ways in 2021.

A report in October by the New Economics Foundation indicated more than half of the €242bn of corporate bonds held by the ECB at the end of July were from companies in carbon-intensive sectors.

Christine Lagarde, the ECB’s president, said a few days later that the bank was considering using its asset purchases to help in the fight against climate change — and Isabel Schnabel, an ECB board member, asserted this even more strongly in September.

“The ECB tailoring their programme to exclude carbon-unfriendly issuers — I don’t think that should be taken with a pinch of salt,” says Bhimji. “Statements made by the ECB tell me they are becoming more conscious in their bond buying, and bonds issued by companies that are still very far away in ESG objectives will struggle.”

This could introduce new pricing tilts, between industries and within them.

“A regular bond by a northern European energy company like Total or Shell will be a more difficult sell,” says Bhimji. “Quite a few northern European utility names still have very bad carbon ratings, whereas Spanish and Italian names surprisingly perform very well. Now, you’ll have a bigger bid on the periphery names, so that spread could narrow.”

The ECB may also decide to favour labelled green bonds over plain ones.

There are already clear distinctions in spread between types of themed bonds. Green bonds trade most tightly, followed by sustainability-linked bonds, whose proceeds are not earmarked for green projects. Conventional bonds trade widest.

Sustainability-linked and transition bonds are new products that are still being defined — this is likely to accelerate in 2021 as they gain adherents and become more familiar.

The Green Bond Principles put out guidance on transition finance in December, indicating transition bonds could be issued with either a use of proceeds or sustainability-linked structure.

“You’ll see an increasing amount of transition bonds being issued from carbon-heavy companies,” says Baldini. “Investors would prefer to see sustainability-linked bonds that also align the use of proceeds, otherwise some investors believe that the company is only making a gesture.” GC