When Peru sold $4bn of bonds in November, including a century tranche, despite having had three presidents in two weeks, treasury director José Andrés Olivares found symbolic comfort in a $15bn order book. The amount surpassed, noted Olivares, the unprecedented $12bn or so that that government needed to raise in 2021.

“Almost all LatAm governments are predicting they will have to issue more than before, as they need to finance large deficits and economic stimulus,” says Cristina Schulman, head of Latin America DCM at Santander.

Coronavirus hit Latin America’s already underperforming economies disproportionately hard. According to Goldman Sachs, the region’s seven largest economies account for 6.7% of the world’s population, yet almost a third of coronavirus deaths.

This has meant longer lockdowns than elsewhere, requiring governments to “spend a lot more money for an extended period of time”, notes Lisandro Miguens, head of Latin America DCM at JP Morgan.

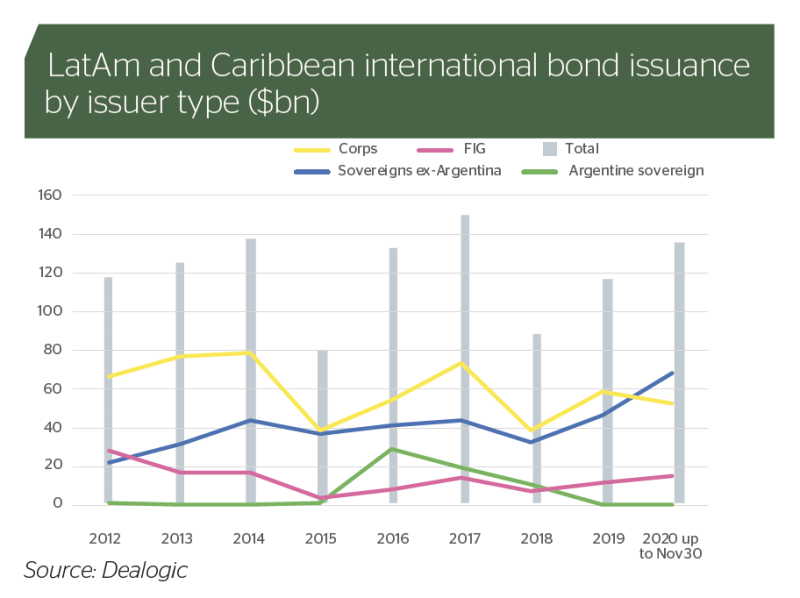

Bond markets stepped up to the challenge when LatAm sovereigns most needed them. By November 30, Latin American and Caribbean sovereigns had sold $67.8bn of international bonds in 2020 — up from $46.29bn in the whole of 2019, according to Dealogic. With more deals due in December, volumes will beat the $70.3bn record set in 2016.

Moreover, says Miguens, “the cost of capital is at almost record lows for many LatAm issuers”, thanks to a very constructive technical backdrop.

The question is whether that technical backdrop can withstand a continued deterioration in fundamentals. Goldman is forecasting a 7.5% regional contraction in 2020 that will “erase the growth accumulated over the last six years”.

“As long as there is strong liquidity and low rates in the US, Latin American bond markets will enjoy strong technical support, without too much focus on fundamentals,” says Miguens. “The risk is the US interest rate outlook: the moment interest rates in the US start to pick up, we can see a reversal of flows and investors may begin to demand structural reforms from Latin American governments.”

Ticking over

Latin America should be grateful that there are few signs that developed market central banks will withdraw support.

Though Goldman predicts the region will grow 4.5% in 2021, this rebound “should not be mistaken for a pathway to robust socially-enfranchising growth thereafter”. The bank’s economists say the region must “embrace productivity-enhancing reforms” more than ever. This will be hard.

“I am not wildly negative on Latin America, but any positivity will come at the margins,” says Sarah Glendon, senior Latin America analyst at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. “I would not expect much by way of reforms or fiscal consolidation except in places that urgently need it or have no choice, like Costa Rica. It will be a year of healing, and if the global liquidity environment stays stable, most LatAm countries will be able to finance themselves. But mostly there will be a continued uptick in debt ratios.”

The political calendar does not favour reforms, with upcoming presidential elections in Peru, Ecuador, Chile and Honduras, and mid-terms in El Salvador, Mexico, and Argentina.

“I expect something of a populist shift in response to the crisis,” says Glendon.

The pandemic has exacerbated social pressures in the region that even affected top-rated Chile, where protests led to a vote for a new constitution. But investors are likely to support stronger names as they rebuild buffers used up this year.

Graham Stock, head of EM research at BlueBay, says he is “not particularly concerned” about the risk of stronger credits veering off course.

“Some countries — such as Peru and Chile — have had a tough time during the pandemic but had a good starting position and therefore fiscal space to respond,” he says. “At the margin Chile will have higher levels of public spending, but that’s appropriate for its income level, and all indications are that the [constitutional] process will be managed properly.”

As for Peru, second on the LatAm rating scale at A3/BBB+/BBB+, even a populist president will not be able to control Congress, says Stock.

Further down the investment grade ranks are Colombia, which is “on notice” about slipping into high yield, and Mexico. Yet both countries “still have relatively low debt to GDP ratios and can sustain higher debt levels”, says Stock.

After issuing heavily in dollars, some stronger LatAm sovereigns may even be able to return to their pre-coronavirus strategy of de-dollarising debt, says Schulman. “Chile’s peso issue in November was promising as it had more international participation [48%] than expected,” she says.

While most LatAm sovereigns already trade tight to pre-coronavirus yields, there is a duality to the market. For certain credits, no amount of positive sentiment can hide their stress. While new issuance breaks records, Argentina, Ecuador, Belize and Suriname all restructured bonds in 2020. Others may follow.

“Individual countries will run into trouble in 2021 if they can’t access financing,” says Stock. “Costa Rica, in particular, has large financing needs next year and cannot seem to agree on a policy framework that would allow it to attract funding. We don’t think that situation is likely to change, so a restructuring is a real risk.

“El Salvador and Bolivia are also in difficult situations, though I do not think they will default next year.”

For these countries, political infighting is perilous — especially when, as in Costa Rica’s case, consensus is needed to approach the IMF and avoid a funding crisis.

Glendon says the IMF is mostly acting “generously”, highlighting Ecuador’s front-loaded facility and the Fund’s view that 2021 is a year for recovery — not fiscal consolidation.

“Whatever programmes the IMF put in place will reflect this position,” she says. “It is in Costa Rica’s hands to reach an agreement palatable to the population.”

Corporate resilience

While no sovereign escaped the economic slowdown, LatAm companies offered a more nuanced opportunity to play the pandemic.

“This year we sought to be in credits offering both good carry and protection from the economic decline,” says Jennifer Gorgoll, co-lead portfolio manager, EM corporate debt at Neuberger Berman. This meant sectors like TMT and consumer, and in particular Brazilian and Mexican food companies. “For 2021, our focus will be on companies that should rally as the economy rebounds.”

Gorgoll says that the EM corporate default rate will end 2020 around 3.5% — below even the pre-pandemic forecasts of 5%-6%. And for 2021, she expects 3%. JP Morgan’s EMBI Diversified sovereign bond index had returned 3.2% as of late November. The CEMBI — which measures EM corporates — had returned 5.26%.

“Though the quality of corporate credit has deteriorated, I like to think we have passed the trough,” says Gorgoll. “Companies have been able to push back maturities, and defaults have been far lower than expected.”

It helps that, beyond a handful of Argentines, there are few corporate issuers in Latin America’s most stressed countries. But though Schulman says the market remains “selective” when it comes to credits badly affected by the pandemic, the market’s development has continued apace.

“We are seeing more brand new issuers — a lot of which are family-owned businesses and are often good companies,” says Gorgoll. “High yield has demonstrated that it is here to stay and will continue to grow.”

After established names dominated LatAm’s corporate market when the pandemic hit, a slew of first-time borrowers caught the eye in the autumn. Brazilian retailer Lojas Americanas (Ba1/BB/BB) in September, and its digital subsidiary B2W in November, enjoyed well received international debuts despite being domestic businesses operating in local currency.

Miguens at JP Morgan sees potential for new supply from companies wanting to take advantage of low interest rates internationally, at the expense of local markets. “This will especially be the case if we see the dollar weakening, as many analysts predict, giving companies greater comfort about currency risk,” he says, adding that he is also expecting increased M&A activity to lift loan and bond volumes.

Domestic bond markets in Peru and Chile could be affected by laws allowing citizens to make early withdrawals from pension funds, says Schulman, who also notes that Brazil’s local markets “have not recovered to their pre-pandemic strength”.

“There are companies that might prefer local currency, but do not see local markets offering the size and maturity that they want,” says Schulman. “This could especially be the case for companies linked to the consumer space.”

On the buyside, Gorgoll backs this view, saying potential LatAm FX strengthening is making local bonds attractive, and meaning she is “not afraid of domestic-focussed companies that benefit from both the weakness of the dollar and the rebound in the economy”.

There is one other external driver that both Gorgoll, who has been adding exposure to LatAm metals and minings companies, and Stock, on the sovereign side, hope could paint a rosier picture as LatAm wades through the pandemic fall-out.

“If the rebuilding effort in the US and China, in particular, involves infrastructure it could strengthen commodity demand and be very useful for LatAm governments,” says Stock. “That is the one wild card that might lead to better-than-expected performance in the region.” GC