A very simple conclusion could be drawn from the global financial crisis in 2008/2009 — banks lacked capital.

In response, the Basel Committee came up with a new set of standards that would require financial institutions to build up capital buffers on top of their minimum targets.

The idea was that these buffers should be respected in the good times but could then be released in periods of stress, as a way of giving lenders more room to absorb losses or expand their loan books.

The buffer system has been put through its paces for the first time in 2020, as the coronavirus crisis ravages the global economy.

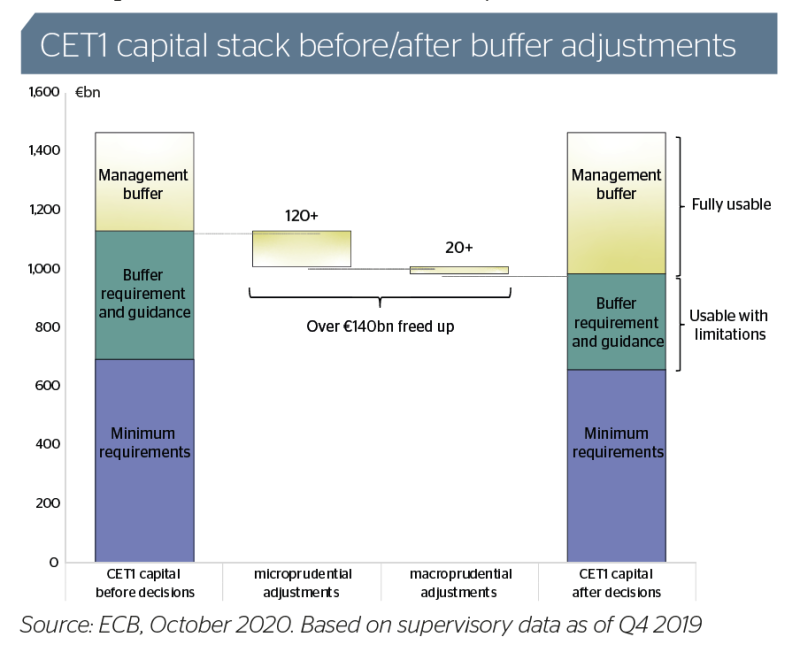

At first glance, the Basel III rules seem to have passed their test with flying colours. The European Central Bank said in June that it had helped to release €610bn of capital by allowing banks to operate below their buffer requirements — a far-cry from where the sector had stood in 2009.

But there is now growing concern over whether lenders can actually use the resources that are supposed to have been freed up.

Despite the encouragement from their supervisors, many banks seem intent on keeping their capital ratios as high as possible during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Common equity tier one (CET1) levels have even risen by about 50bp in the EU, according to company reports for the nine months through to October.

“We are still waiting for the real economic impact of the crisis to materialise on banks’ balance sheets and capital, so there remains some doubt over what will happen,” says Charles-Antoine Dozin, head of capital structuring at Morgan Stanley in London. “But if we look at their recent communications, many of them are signalling that they have no intention of breaching their buffers. This part of the policy response has been ineffective.

“There are some elements of the capital construct that we need to rethink in light of the crisis.”

Change in danger zone

Doubts about the usefulness of bank capital buffers are set to underpin a lively policy debate in the coming months.

Some of the battle lines have already been drawn, as stakeholders try and single out reasons why lenders may feel unable to deploy their rainy-day funds.

A key factor relates to pressure coming from the financial markets.

When the ECB spoke about unlocking €610bn of new capacity for lending earlier in 2020, nearly a third of its figure related to resources that are tied up in combined buffer requirements (CBRs) — a very important threshold for investors.

Firms are legally required to calculate their maximum distributable amount (MDA) if they fall below their CBR, regardless of any guidance issued by supervisors.

This can then lead to restrictions on equity dividends — which is part of the reason the ECB jumped the gun and effectively banned them in 2020 — as well as on discretionary bonuses and on additional tier one (AT1) bond coupons.

“It has been interesting to see that the MDA debate is not only about dividends, it is also about AT1 coupons,” says Dozin.

“Fixed income investors have come to expect that issuers maintain an MDA buffer so they can continue making their AT1 payments. That has proven more important for banks than having the flexibility to use their buffers.”

The UK has already suggested changing MDA rules during the pandemic, with the hope of creating more room for manoeuvre within the framework.

Under the terms of the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR II), a bank cannot reward its investors if it breaches its CBR at a time when it is also making losses.

After Brexit, the Bank of England plans to give firms more space to make distributions by allowing them to use their last four quarters of profit when calculating their MDA.

Market participants hope the EU could follow a similar policy path in 2021, but progress is unlikely to be anywhere near as swift.

“There could be changes to the MDA rules in the next legislative cycle, like we are seeing in the UK,” says Kapil Damani, head of capital solutions at BNP Paribas in London. “But it’s possible that Europe will need to see more of an international consensus before taking the next step.”

Global standard setters like the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Financial Stability Board have come forward to highlight the need to address “impediments to buffer usability” during the pandemic.

But so far they have stopped short of issuing their own policy recommendations, preferring instead to wait until they can get a better understanding of the impact of the crisis.

“The question of whether the flexibility provided by authorities is actually used by financial institutions may require particular attention,” the FSB said in its annual report in November.

What goes up must come down

As well as considering how to allow banks to move below their capital buffers, policymakers will also want to reflect on whether there are any problems with the buffers themselves.

Europe has introduced a number of macroprudential requirements within its capital framework. But only one of the targets — the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) — is specifically designed to be released in a downturn.

“Only a handful of countries had built up countercyclical capital buffers going into the crisis,” says Damani. “You could argue that a lot more should have been done in advance.”

According to the Single Supervisory Mechanism, CCyBs made up just 0.1% of risk-weighted assets in the euro area before the pandemic.

Far more capital went towards meeting targets like the systemic risk buffer (SyRB) and the buffer for important institutions (O-SII). But these requirements are more structural in nature, making it harder to justify their release in times of stress.

Santiago Fernández de Lis, head of regulation at BBVA in Madrid, says the system is “not working as well as expected”.

“There is an interesting debate around the need to rebalance capital buffers, increasing the countercyclical part of the buffer and reducing the structural parts in compensation,” he says. “This is something that will need to happen.”

Macroprudential buffers are still set by national authorities in the EU, rather than being handled by the SSM.

The approach makes fragmentation more likely within Europe. While some supervisors, like the Dutch National Bank, have now committed to switching their bias towards countercyclical capital, other member states could easily stick with their status quo after the pandemic.

José Manuel Campa, chair of the European Banking Authority, has therefore asked whether more could be done at the supranational level.

“Since countercyclical buffers have been built up only in a limited number of jurisdictions and to relatively limited levels, the question is whether we should harmonise the way these buffers are deployed, pushing for a faster and larger accumulation in good times,” he said in a speech in September.

Beyond the quick fix

Debate over bank capital buffers will soon start to turn into action in 2021.

Market participants expect the European Commission will publish a new draft of the EU’s rules on capital requirements in the first half of the year, if not in the first quarter.

The proposals for CRD VI/CRR III had been expected in early 2020, but the legislation was delayed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The package is primarily going to be looking at what we call Basel IV, but it is also an opportunity for the legislator to make some tweaks and modifications around the edges of the capital rules,” Dozin explains.

“There is a history of using the review of a level one text to fix problems that have been identified in the framework or provide clarifications.”

Law makers have already shown that they are prepared to revise some rules and regulations as a way of encouraging banks to boost their lending in a stressed economy.

MEPs agreed on a series of amendments to the CRR in the June, for example, offering what the Commission described as a “quick fix” in the heat of the crisis.

Now the focus will need to move towards finding longer term solutions to some of problems that have been encountered over the last year.

The discussions are still likely to be underpinned by uncertainty. Economists do not have a full sense of the cost of Covid-19, which will only become clearer when government guarantee schemes, payment holidays and other support measures have ended.

But banks are eager to know more about what life could look like after the pandemic, with policymakers and supervisors yet to have offered much in the way of detail on their exit strategies.

“Nobody wants to start the Basel III debate all over again, but there will be some changes,” says Fernández de Lis. “We have to figure out what the new steady state should look like and how long it might take to get there. It is a very complex exercise.

“A crisis as big as this one will not be solved by returning to business as usual.” GC