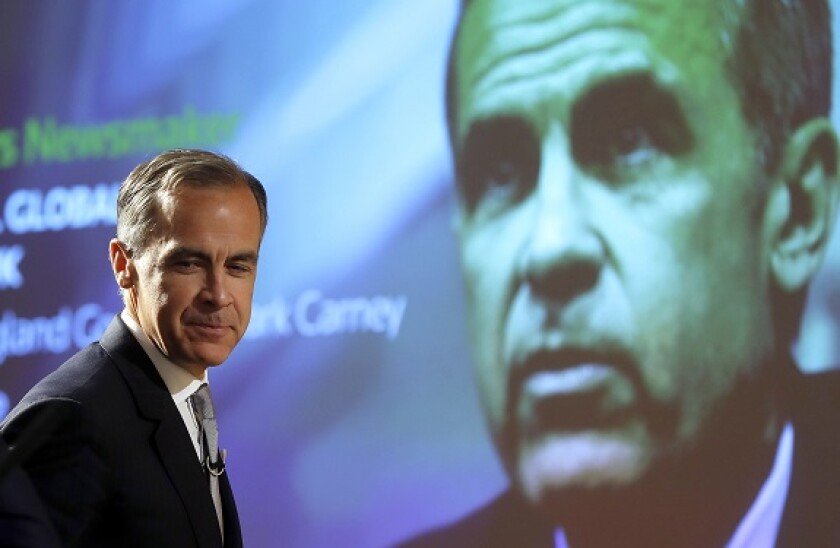

Mark Carney has been busy since leaving the Bank of England where he was governor. He has continued his work as a UN special envoy on climate and finance and adviser to UK prime minister Boris Johnson for the COP 26 meeting, has launched a taskforce aiming to develop a voluntary carbon market, and has been snapped up by Brookfield Asset Management to be vice-chairman and work on its environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment strategy.

The suave Canadian is also now on BBC Radio 4 giving The Reith Lectures, where he talks about the dichotomy of value versus values. It is an economist's look at the limitations of market systems in efficiently delivering social outcomes and the triumph of "market sentiments over moral sentiment".

The first lecture introduced this theme and the second explores how this trend shaped our response to the 2008 global financial crisis. The third, which airs on next Wednesday, deals with the reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic. The fourth will tackle a topic close to Carney's current work: the climate crisis.

He doesn't mention it, but the idea of a water futures market — reported on here by Rosie Frost at euronews Living —might make for interesting context.

Futures exchange CME has started offering the ability to trade contracts based on Californian water market. Each contract represents 10 acre feet of water.

Carney points out that creating a market in something — attaching a price to it — defines its value. This can be counter-productive: he cites a famous experiment whereby children were challenged to raise money for charity. Those who were given no incentive beyond helping the charity raised more than children given a financial incentive.

Carney's tenure as governor of the Bank of England — from July 2013 to March 2020 — neatly lay between two crises, although of course he did grapple with the impact of the Brexit vote. For the rest of us, well, we are not sure it's actually possible to become addicted to crises (although we seem to be experiencing them more regularly) but certainly there are feelings of nostalgia for old ones.

This is only natural: the current one always feels significantly worse and more complicated than the previous version, where you have the benefit of hindsight.

So here's a trip down memory lane via a fascinating conversation between two central actors in the great financial crisis of 2008: UK chancellor Alistair Darling and his permanent secretary Nick Macpherson. Lovely bits of insight include Gordon Brown's 5am starts, Conservative politician Ken Clarke's dislike of meetings before 9.30am, the age of deference being dead and Royal Bank of Scotland's chairman calling the Treasury to say his bank had just three hours left of money.

But the real juice is the discussion around the crucial working relationship between the two men in No. 11 Downing Street and how they worked with No. 10 Downing Street., and how little difference there actually was between the Labour government and Conservative coalition in their responses to the crisis in terms of austerity and public finances.

Macpherson, in praising the British system of discipline towards crises — saying that whenever it has looked over the edge it has always pulled itself back from letting public spending rip out of control — probably thought he was on safe ground when the show was broadcast in September 2017. "You cannot run a deficit of 10% of national income year in year out without turning into Argentina," he said. Well, fast-forward to December 2020 and the UK government is running a budget deficit of 19%. Oh, for a return to 2008. Crises were so much simpler then.

Back to the topic of ethics, values and professional norms are typically assumed to overlap. In the legal profession, the universal right to counsel is an unassailable principle, and accordingly, lawyers like to hold themselves above scrutiny for their choice of who to defend.

Alex Pareene challenges that notion in The New Republic, highlighting US attorney Neal Katyal's recent case in front of the Supreme Court in which he argued that children enslaved on cocoa plantations should not be allowed to sue companies if they aided and abetted their slavery. Katyal, incidentally, is a prominent Democrat.

In today's climate of corporate social responsibility, private companies are expected to show some deference to codes of ethics beyond maximising shareholder value, yet the legal profession still sits behind an ethical force-field, separating them from the consequences of their arguments.

Obviously the judicial system relies upon the willingness of lawyers to defend anyone, but of course, Katyal is not willing to defend anyone. He is willing to defend the small circle of people who can afford Hogan Lovell.

Finally, back to the UK, where one small mercy amid a rampant second wave of coronavirus infections is that we are not dealing with panic buying of survival essentials — and, err, nice extras like super fine 00 grade pasta flour.

Those of us in the country remember only too well the crazy queues snaking round the supermarkets, as people rushed to get their hands on toilet paper, bottled water and hand sanitiser. Instead, this time around the demand surge is elsewhere, notably in the Scotch Egg market, as Donna Ferguson reports in The Observer.

This hitherto humble, peculiarly British snack (a boiled egg wrapped up in a ball of sausage meat and breadcrumbs — think of it as a working man's Turducken) has suddenly found itself centre stage.

How so? The UK government has ruled that you can only visit a pub in much of the country if you are having a substantial meal. Step forward the Scotch Egg, now the nation's favourite accompaniment to the Great British Pint. The problem comes after the third pint — four Scotch Eggs is really going some. We recommend finding a dog-friendly pub: and a hungry dog.

Additional reporting from Jasper Cox