It’s been a long wake-up call, and a costly one. A lot of energy has gone into instruments that do not create new green investments in the real economy, but merely advertise them.

Investors love to feel they are doing good. Green bonds help with that, but describe only a corner of the issuer’s balance sheet. They do not protect investors from the risk or responsibility of its other activities.

Adventurous issuers and investors have seen that most of the economy is not green, and the labelled debt market ought to be addressing that. Hence the urge for transition bonds.

But how to get them right? Some fear they could be a soft option for companies half-hearted about becoming green.

The green debt community has made an admirable attempt to set up transition bonds as a robust and worthwhile market.

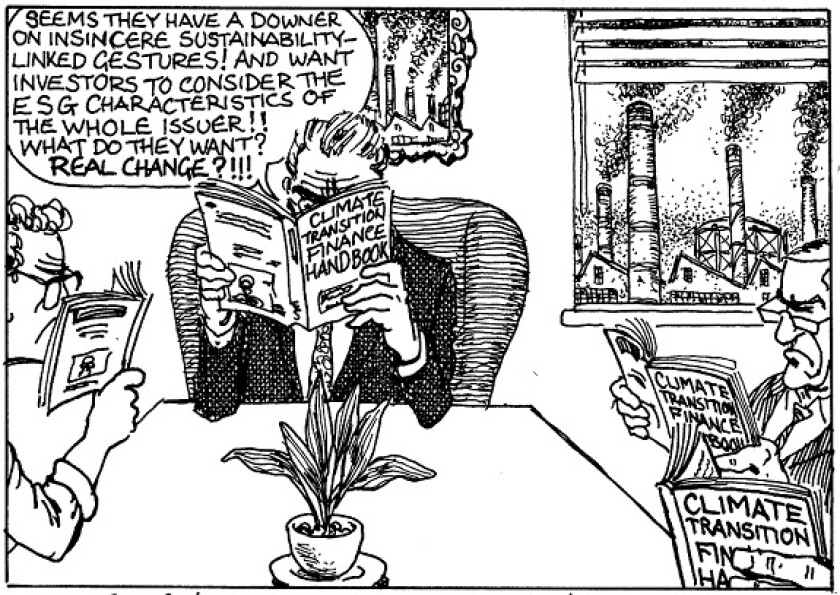

The Climate Transition Finance Handbook, published this week, gets two things right. First, it emphasises that issuers should demonstrate their transitions are science-based and will lead to fulfilling the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming.

Second, it focuses less on a debt instrument, such as a green or sustainability-linked bond, which only gestures weakly towards a greener future.

Instead, it calls for what investors should have done all along — consider the ESG characteristics of the whole issuer, above all whether it can change fast enough to align with the drastic changes the economy needs.

Not all transition bonds will be good. That is the point. Investors will learn to ask tougher questions. Transition bonds are the adult form of green bonds.