His premise is likely true: the smaller the margin of saving that EU loans offer countries versus capital markets, the easier it is for the eurosceptics in those countries to argue for preserving their fiscal sovereignty and not ending up in hock to the bloc.

The loans in question are those offered by the EU’s recovery and resilience facility, part of the €750bn coronavirus recovery fund. The aim of the instruments is to provide countries with a cheaper way to finance the spending required to kick-start their recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

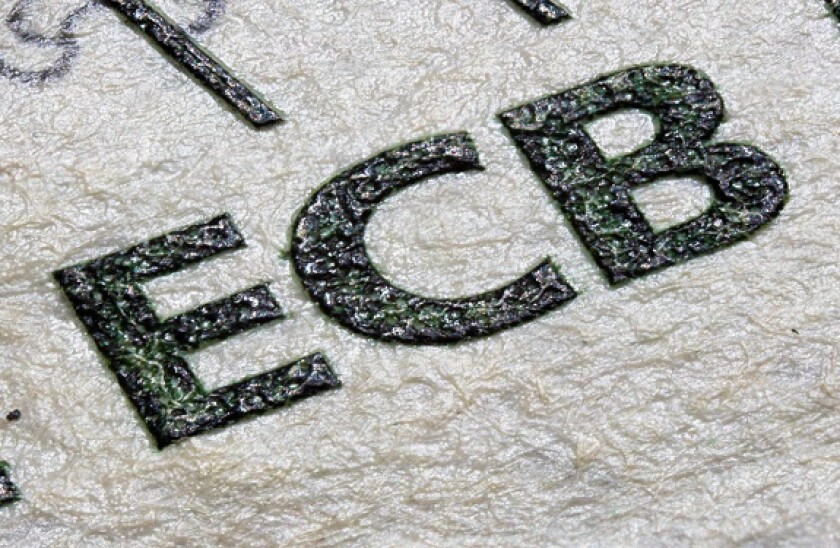

But Mersch seems to be saying that the ECB has a duty to push eurozone member states into taking EU loans and the oversight that comes with it.

Certainly, he is a fan of greater political integration. "So far, the political dimension of the EU's integration has been the most neglected," he wrote in October. "Shifting competences to the European level needs to be accompanied by further political integration and democratic accountability."

But if countries decide not to use the loans, then that is between their government and their electorate. The electorate might take issue with spending more tax than necessary on debt servicing but equally, they might take issue with giving the EU greater fiscal oversight. Whether the debt service saving is worth the EU’s oversight is a calculation that should be up to each individual member state.

In any case, those loans will not become available until late 2021 or 2022. Before that, the ECB’s monetary policy support has been absolutely vital in ensuring countries have the market access they need to support their economies through the crisis.

That extraordinary support has brought down periphery government bond spreads to Bunds (and to the EU’s curve) to all time lows, meaning that the ECB has indeed lessened the attractiveness of EU loans.

But suggesting that this is an argument for the ECB to amend its programme is a case of saying the quiet part loud. Mersch effectively calling for the ECB to lean on the scales is nothing less than an attempt to press monetary policy into the service of a political agenda: the promotion of EU integration.

There are plenty of reasons to hope that countries do take EU loans. First, for many countries, they will be the cheapest way to finance their recovery. Secondly, the more EU debt outstanding, the greater the opportunity for it to become a de facto eurozone safe asset and promote the international role of the euro. Thirdly, and most contentiously, perhaps more centralised fiscal control in Europe is no bad thing.

But evaluating those benefits is the right of each member state.

As an ECB governing council hawk of long standing, it seems likely that this is simply Mersch's newest angle to criticise the ECB’s policy of negative rates and quantitative easing programmes. In future, he would do better to keep his criticism to considerations that lie within the ECB’s mandate.

It is not necessarily wrong for the ECB to withdraw some of the support it has been extending, although one might fairly say that the middle of a pandemic is not the moment for it. Certainly, there are plenty of hawks who would make the case that they should have done it already. But what is unequivocally wrong is to do so in order to promote EU loans.

The idea of the supposedly technocratic and independent ECB amending its policy to increase the cost of debt for its members to encourage them to take EU conditional loans looks an awful lot like the sort undemocratic manipulation that the Brexiteers and the Five Star Movement have been claiming to identify, and with great success.

Regardless of what lay behind Mersch's comments, by advancing them he probably does more to hurt the cause of EU integration rather than help it. But in any case, let us hope that ECB chair Christine Lagarde recognises it as such, and takes the first available opportunity to put the idea to rest.