Lots of countries have bungled their attempts to manage coronavirus, but at present the US looks to be faring worst of the major economies.

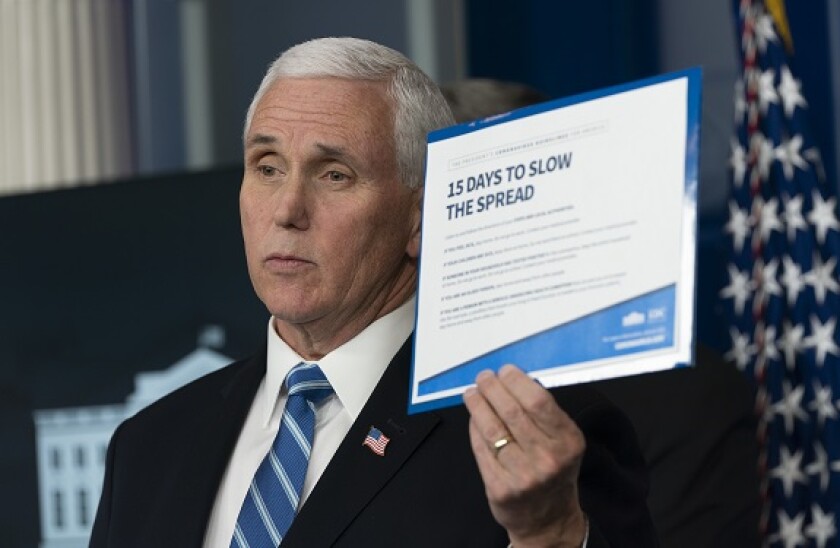

With the death rate on a similar trajectory to European countries, on Monday and Tuesday Trump was speculating about reopening the US for business in the coming weeks. This would have disastrous consequences for public health, given the lack of effective testing and tracing measures that would mitigate such a relaxation of social distancing.

Luckily, other layers of government and businesses have some power to decide their own policies, regardless of what Trump thinks.

The US has also delayed in agreeing a stimulus plan, with Democrats having attacked Republican proposals as not doing enough for workers.

Other countries cannot depend on the US for global leadership either, and not just because of its complacency about the health crisis in its own country. Trump reportedly tried to pay German scientists working on a vaccine for exclusive rights to their work, as he attempted to secure a vaccine solely for the US.

A time traveller surveying how the US government has responded to the pandemic would be surprised if you told them that international companies and investors had been scrambling to get hold of the US currency in recent weeks, which has even risen in value against other safe havens like the Japanese yen and the Swiss franc.

The dollar’s global crown is intact, despite various suggestions over the years that the renminbi or the euro could challenge it.

In October 2018, Kalin Anev Janse, secretary general of the European Stability Mechanism, told Croatia’s Lider magazine: “The question we get asked more and more is how to make the euro more global as the dollar is becoming a political instrument and the US is retrenching from global trade. There’s a growing demand for a stronger second currency, and that’s the euro.”

There is little evidence these questions have found an answer. According to the Bank of International Settlements’ latest statistical bulletin, at the end of the second quarter of last year, non-bank, non-US borrowers had $11.9tr in dollar-denominated credit outstanding. By contrast, non-bank, non-eurozone borrowers had just €3.38tr in euro-denominated credit outstanding.

And in recent weeks, corporates have been drawing down dollar credit lines and borrowers have outpaced supply in short-term dollar funding markets. Longer-term dollar funding is also under pressure, particularly in emerging markets.

The Federal Reserve has acted to the benefit of the world by cutting rates sharply, bringing out various new facilities day after day to ease market pressure, and setting up swap lines with other central banks.

It is not in the Fed’s interest to have a surging dollar that suppresses domestic inflation, and it is not in Trump’s interest either, given his obsession with the current account deficit.

Still, a nationalist country holding the most global and important of currencies is bound to risk instability. You cannot separate the two, most obviously through the ability of the government to use the dollar for sanctions.

Recent weeks have also highlighted how the world still depends on the Fed and US-headquartered banks in order to access hard currency, borrow and service debt.

These institutions do not exist in a vacuum separate from US politics. The current crisis in particular has led central banks and governments, including in the US, to collaborate more forcefully in the recognition that the one needs the other.

Before the current turmoil, the Fed had come under plenty of attack by the Trump administration for its interest rate policy, and had delayed in joining the Network for Greening the Financial System, an initiative populated by its peers. It is hard to imagine it is ever completely shielded from political pressure.

One test of the ability to separate nationalist politics from international central banking is the provision of dollars through swap lines. The Fed has passed the exam so far. But the Institute of International Finance, an industry group, recommends that it be open to expanding its lines to other jurisdictions. “The US dollar is in a privileged position as the world’s reserve currency,” it said. “With this position comes the responsibility of keeping the global financial system stable.”

Would the Fed countenance opening a line with a country the US president is in a serious dispute with? Pierre Ortlieb, economist at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, wrote earlier this month that the absence of a swap line with the People’s Bank of China “may be a blessing in disguise”, because the “politics of providing direct liquidity to the Chinese banking system and to competing firms would probably preclude use of the swap lines”.

There can be no uncoupling of the US and the dollar, conscious or otherwise. Without US politics becoming less dysfunctional, or the dollar being challenged, we are in for a bumpy ride.