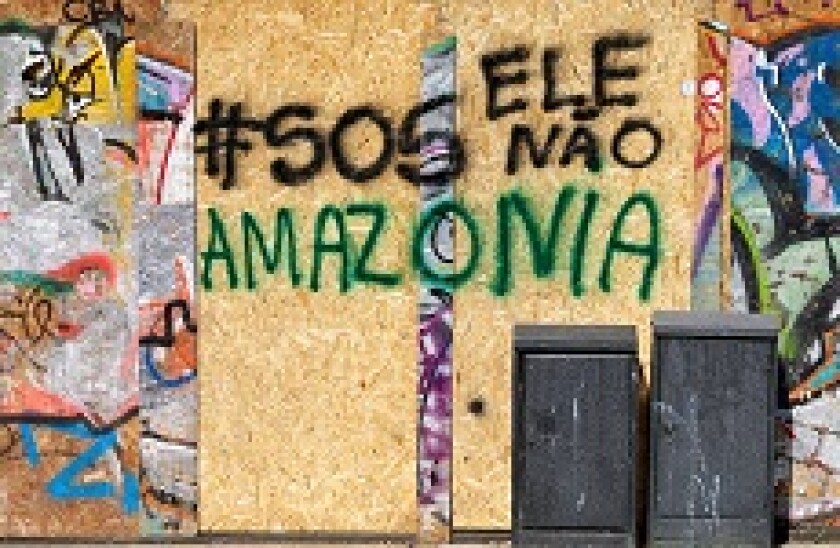

Deforestation in the Amazon reached a decade-high level in July, and in the past days fires burning through the forest have alerted the world’s media, celebrities and politicians to Brazil’s environmental plight under far-right president Jair Bolsonaro.

Without evidence, Bolsonaro has accused non-governmental organisations of causing the fires in order to embarrass his administration, which took power at the start of the year and is critical of environmental legislation. On Tuesday, it rejected an offer of aid from the G7 countries to help fight the fires.

Bolsonaro’s environment minister says the Amazon should be “monetised” through opening it up to development, while enforcement actions by the main environmental agency reportedly fell by 20% in the first half of the year.

Much of the pressure to destroy the Amazon rainforest comes from Brazil’s agricultural sector, and farmers are thought to have started many of the fires in order to clear land.

Those with financial means who want to combat climate change and environmental destruction are encouraged to invest in funds with clear environmental policies, providing capital to green projects. But these well-meaning investors would be surprised to learn that the Brazilian agricultural sector has been a key issuer of debt labelled “sustainable”.

A problem of cows

A month ago, beef producer Marfrig issued securities that it alternatively labelled “sustainable bonds” and “sustainable transition bonds”.

Beef production is not only carbon-heavy, but in Brazil it relies on deforestation. But Marfrig is using the proceeds to buy cattle from the Amazon biome (ecological region) that has not come from deforested areas, areas that violate indigenous land rights or conservation areas.

Marfrig’s ability to follow through on this criteria is questionable: some observers, including Greenpeace, worry that its monitoring process falls short when it buys cattle that were in turn supplied from somewhere else.

Greenpeace actually pulled out of an agreement with Marfrig in 2017, blaming a lack of political will to deal with issues involving indirect suppliers.

Marfrig can argue that it is moving towards sustainability, and that it should be rewarded for doing so. But beef production will never solve climate change: it can only do damage of varying degrees. Marfrig can move from being a very dirty issuer to a less dirty issuer, but it is hard to see how it can be a genuinely green one.

Some investors did question how exactly buying methane-generating cattle in the Amazon is a green activity, and it is not clear how many buyers of the bond had specific sustainability mandates. But these investors are not the only participants in the sustainable finance sector, and others were willing to support Marfrig’s bizarre “sustainability” label.

BNP Paribas, ING and Santander ran the deal. One syndicator defended it to GlobalCapital, saying the firm “wants to show you how challenging it is in the beef industry, so you can understand how important each step is”. Ratings agency Vigeo Eiris provided a second opinion for the bond (an important procedure in this market) where it said the notes aligned with the four key components of the industry-wide Green Bond Principles and Social Bond Principles.

Distrust in Brazil

This is not the first time that environmentalists have become suspicious of a Brazilian sustainability bond. These types of securities issued by pulp and paper producers in the country provide little added value from an ecological perspective, according to the Environmental Paper Network, a group attempting to make that sector more sustainable.

“They do not initiate a change towards a sustainable economy, but at best only make existing practices less harmful to the environment,” it said in a report in May.

Pointing to one bond issued by Fibria, it noted that almost half of the proceeds spent between 2015 and 2017 were used to buy certified wood, an activity barely mentioned in the second opinion report provided by Sustainalytics.

Sustainable finance has become a big business for issuers, investment firms and their various intermediaries, outpacing regulation in the area. Those in the sector must prove they are green rather than just green-eyed in order to gain the trust of consumers, investor clients and governments.

That requires stringent standards — something that has been missing in Brazil and, it seems, with investors at large.