Investment banks have been quietly hoping that 2019 would be an improvement on a difficult and disappointing 2018 for equity capital markets. Unfortunately, those hopes are now mixed with fears that 2019 could turn out worse.

There is a promising roster of companies seeking to attempt an IPO next year, including Volkswagen’s truck business Traton and Kazakh oil and gas company Kazmunaigas. Among them are several firms that had to abandon their listings in the turbulent markets of 2018, notably Cepsa, the Spanish oil and gas company owned by Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment.

But in place of the buoyant finish to 2018 that market participants had been hoping would drive away the summer blues caused by US president Donald Trump’s aggressive rhetoric — and actions — on trade and fears of Italy restarting the eurozone debt crisis, the autumn saw the darkest spell of the year.

A violent sell-off led by Apple and the four other US Faangs — Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google — has left global equities teetering on the brink of a very deep canyon.

“We are more worried about a bear market than anything else,” says the head of EMEA ECM at a bulge bracket bank. “It becomes very hard to sell anything in a bear market and investors are taking a lot of pain. We are keeping an eye on the US, but I think we might be close to that already in Europe.”

Fund managers who play in ECM deals have suffered heavy losses — some hedge funds are understood to have taken hits of the order of 20% to their portfolios in October and November alone.

That is hardly surprising when the Dax index has fallen nearly 16% from its 52 week high, the Euro Stoxx 50 around 15% and the FTSE 100 about 12%. Analysts consider markets to have entered bear territory when they fall 20% from a 52 week high or over a period of two months.

ECM investors usually aim to beat the market, and indeed, IPOs have performed better than the indices. The 254 IPOs recorded by Dealogic as having been priced in EMEA in 2018 up to late November, totalling €39bn, have generated just over €1bn of profit for investors through share price gains, or 2.6%.

But those figures are flattered by the performance of two deals — medical technology group Siemens Healthineers and Adyen, the Dutch payments processor — which contributed nearly half of all the positive returns. Without the €1.3bn of stock market growth generated by Healthineers, the EMEA IPO market as a whole would have generated a loss for the year.

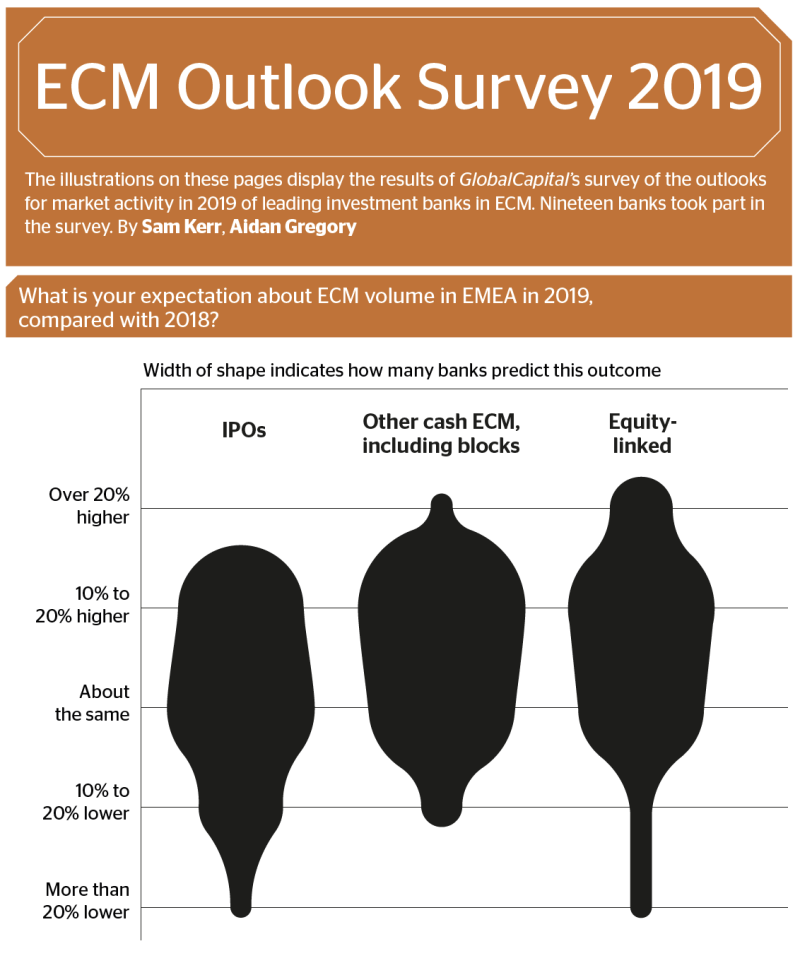

That is one reason EMEA ECM issuance fell 40% in 2018, while global capital raising fell 17%.

As a result, ECM investors are entering 2019 in highly defensive mood. Planning their allocations for 2019, some funds are considering reducing equities and bulking up cash.

Events in the new year could, in theory, reinvigorate their animal spirits. But the horizon is strewn with threats.

Brexit and trade roadblocks

Front and centre is Brexit. Negotiations between the UK and European Union are at a critical stage and the political upheaval in the UK is reaching a crescendo. The range of potential outcomes is very wide, from a second referendum that calls off Brexit, through acceptance of Theresa May’s deal, to a chaotic exit without any kind of agreement and the UK government falling.

But whatever happens, UK ECM issuance is likely to be at best subdued in the first quarter and at worst paralysed.

With Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, warning that a no-deal Brexit could plunge the economy into a “very large negative supply shock” not seen since the 1970s, it is hard to imagine any UK issuer that hopes to attract international demand picking this period to float on the stockmarket — at least until the no-deal risk has been taken off the table.

“If a deal is rejected, then it has different implications for the real economy, the currency and demand for goods and services in 2019,” says Chris Sim, managing director, investment banking at Investec in London. “These effects on ECM could be dependent on sector and the nature of the equity offerings — IPOs, secondaries and blocks. For example, an IPO [of a company] largely dependent on UK consumer demand certainly becomes much more challenging.”

How quickly sentiment towards the UK recovers if a withdrawal deal is reached and attention turns to the no doubt protracted negotiations over future trade ties remains to be seen.

The damage from Brexit should be limited to UK deals, although it does nothing to bolster confidence in the stability of the EU.

Something no one can avoid, however, is the global trade tension being whipped up by Donald Trump, which did much to unsettle investors in 2018.

The US and China have already imposed numerous restrictions on each other, but this could be escalated in January, when Trump has threatened to raise the tariff to 25% on $200bn of Chinese imports. He is already talking about a “phase three” should China retaliate, although the G20 meetings in Argentina did see some rapprochement between the two sides.

Sucking out money

If trade wars were not enough, the stockmarket is battling rising interest rates, which are explicitly designed to take the heat out of the economy.

“Brexit and trade wars are two major issues which will affect markets but I think interest rates will also play a part — the Fed meeting in December [expected to bring a rate rise] could have a significant impact on market activity,” says James Manson-Bahr, head of EMEA equity syndicate at Morgan Stanley in London.

An ECM head in London says some quant funds immediately re-allocate from equities to bonds as soon as the 10 year Treasury hits a certain level.

This was partly blamed for sparking the October sell-off.

“US rates are a big focus for us,” says Sim. “Seeing US data come out, particularly on employment, it looks to us like the US economy is running close to capacity. Therefore, we think the 10 year yield will continue to track higher and that will increase valuation pressure across the board, particularly in equities.”

Meanwhile in Europe, the safety net of quantitative easing is being folded up. “In an environment where the Fed is actively taking liquidity out of the market, rates are going up and QE in Europe is tapering down, the market is likely to react more violently to uncertainty,” says Martin Thorneycroft, head of cash ECM at Morgan Stanley in London. “There is also some evidence that growth in some of the major economies is slowing down and that is another elephant in the room for markets.”

End of the cycle

All these indicators are provoking concern that 2019 could bring a fully growling equity bear market — something that all market participants know is coming one day.

It is not a given yet. “The recent volatility, which we saw from mid-2018 and perhaps earlier, is clearly something which has characterised this part of the cycle,” says Claudia Panseri, an equity strategist in the chief investment office at UBS Wealth Management in Zurich. “Usually you have rising volatility with a change in monetary policy, which is what we have had. We also have seen some tightening in financial conditions and some slowdown in Asian growth. So volatility is rising, but I don’t think this will lead to a bear market. For a bear market you need a recession and we are not expecting a recession in 2019.”

A severe bear market, of course, would be a nightmare for banks trying to sell IPOs, or any other large equity trade.

Nevertheless, even if the bear does not appear in 2019, conditions will be more difficult. Few believe the violent volatility of 2018 is an aberration.

“US rates going higher when combined with a general slowdown is a concern, as is any pressure on earnings,” says Sim.

“We are seeing some sectors that have had a very difficult three to four years’ recovery, such as oil and gas. Therefore, there will be pockets of opportunity, but overall we do see 2019 as being a more challenging year.”