It is never nice being forced out of your job. Particularly when you think you should be the one in charge. So spare a thought for Thierry Derez.

The CEO and chairman of French mutual insurer Covéa left his position on the board of compatriot Scor in November, after the latter rebuffed Covéa’s bid for a merger. Scor is still holding out — but Derez could end up having the last laugh, if the M&A spree in the European sector catches that insurer as well.

The ground is shifting everywhere: some firms are merging and others are breaking up; some companies are shedding lines of business while others are picking them up.

In the first half of 2018, the value of insurance-sector M&A reached €37bn globally, according to Willis Towers Watson. This was the biggest start to the year since the financial crisis.

As well as keeping insurance insiders on their toes, debt capital markets specialists have had to watch closely, since much of the financing for these strategic shifts has come from bonds.

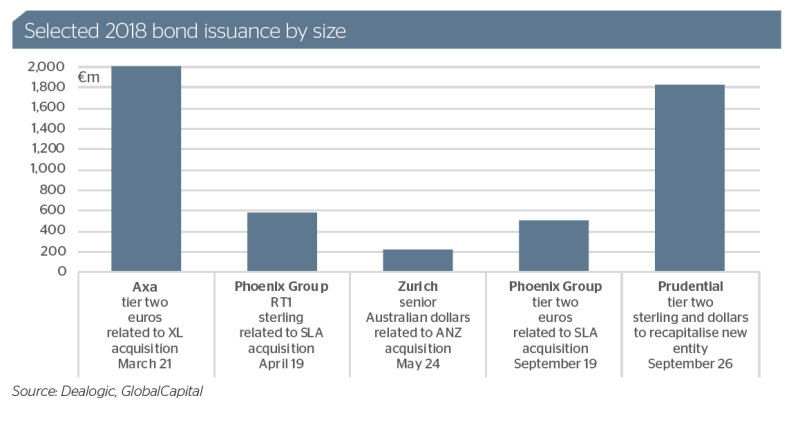

And it has driven overall insurance bond supply, with many of the largest transactions of the year resulting from these changes, rather than business-as-usual financing, including Axa’s €2bn tier two, Phoenix Group’s restricted tier one, and Prudential plc’s triple-tranche tier two (see chart).

The ambitions bringing about 2018’s activity, including a desire to diversify, realise capital efficiencies and meet investors’ demanding expectations, are unlikely to change anytime soon.

Strength in diversity

This creates an incentive for insurers to diversify, and Axa’s acquisition of XL Group can be seen in that light. The French insurer bought the Bermudan firm for $15.3bn this year.

The deal gives property and casualty lines of business a greater profile on Axa’s balance sheet, and the firm says it will lower its risk exposure to financial markets.

Diversification brings capital efficiencies, and this comes across in the EU’s Solvency II regime, implemented in 2016. The regulations reward insurers that have a more widely spread risk profile.

“One plus one doesn’t equal two under Solvency II,” says Philippe Picagne, senior European insurance analyst at CreditSights in London. “It doesn’t come as a surprise to me to see all this M&A activity, just simply because when you add two companies together you don’t need the same amount of capital as both of them do individually.”

Indeed, Axa said the XL acquisition “allows for material capital diversification benefits under the Solvency II framework”.

XL also says it can provide Axa with access to alternative capital.

“ILS markets and other forms of capital are starting to challenge the insurance model,” says David Marock, group CEO of Charles Taylor in London. Charles Taylor provides professional services to insurers.

The sum of the parts

Managing the relationship with shareholders is a more general problem in the sector, according to Picagne. “When you are the CEO of an insurance company, it’s very difficult to sell your stock to investors, because they don’t necessarily understand the business profile, what the insurance company does,” he says. “It’s difficult to value it as well, because some companies look like a black box: you don’t know what you are buying.”

This may be having a centrifugal effect, rather than a consolidating one, as large disparate firms seek to streamline.

“The question is: is the equity valuation of the sum of the parts better than the individual parts?,” says Edward Stevenson, head of FIG DCM at BNP Paribas in London. “Quite a few equity analysts and equity investors have looked at the numbers and decided that actually splitting off businesses might increase the share valuation.”

Prudential decided parting ways was best, and opted to split off M&G Prudential, the retirement and savings business operating in the UK and Europe. Prudential plc will focus in contrast on faster-growing lines of business in Asia, the US and Africa.

To capitalise M&G Prudential ahead of the split, the firm raised $2.14bn of tier two debt this year.

Prudential also sold a £12bn annuity portfolio to Rothesay Life. This is part of another pattern of larger insurers shedding legacy books.

“They recognise that while there’s a lot of value in those books, they can’t find ways to grow that type of business,” says Marock, speaking about the general trend rather than Prudential specifically.

Consolidate to accumulate

Phoenix calls itself the largest specialist consolidator of heritage life assurance funds in Europe. This year it acquired Standard Life Aberdeen’s insurance business.

Whereas analysts of insurers concentrating on live books worry about profit generation, the new names have moved the goalposts. When they hold closed books, in essence a depreciating asset, they judge themselves on cash generation instead.

“If one of the big run-off players came out tomorrow and said cash generation is up 50%, but profits are down 50%, people would be delighted,” says Marock. “If an insurer with a live business came out and said that, that would immediately start concerns about their ability to grow and their ability to generate profits over a long period of time.”

The first model has an appeal for debt investors: cash generation is what ensures distribution payments. And the attraction appears to work both ways.

“Often the business plans of the UK consolidators are somewhat like private equity in format: they are sweating equity and trying to make the most of the debt capital markets to finance businesses and books of business in the most cost-effective manner,” says Stevenson.

Some of these firms carry little capital in the form of subordinated debt. This means they have still been able to receive regulatory treatment from issuing the new Solvency II RT1s and tier two bonds, as their quotas for such treatment had not yet been filled.

The broader business strategy is set to grow in importance. Firstly, firms will continue to pick up closed life books, according to Stevenson. Secondly, pension consolidators may themselves consolidate: M&A could bring benefits.

“You need economies of scale there,” says Picagne. “You would reduce your cost base significantly and improve your profitability.”

Finally, the approach could well be copied elsewhere.

“The use of run-off portfolios has been pretty well-established in the UK for quite a long time,” says Marock. “You’ve seen more growth now into continental Europe where it’s become more acceptable.”

It’s not going away

Sector observers wonder whether Allianz will put to bed persistent gossip by landing a weighty M&A deal to give a clear signal to investors of where it is heading. Aviva is mentioned as a potential target.

More broadly, the trends pushing firms to shake up their businesses will not go away: the benefits some see from diversification, others from streamlining, and yet more from telling a different story when it comes to financing.

“I don’t think in any way we’re at the point where the cycle has turned and now we’ll see less M&A,” says Marock. “I think we’ll see more.”

New challenges will face insurers, and this could encourage more churn. The latest International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS 17) could exacerbate equity investors’ bemusement towards some firms.

“Assessing insurance companies will become more difficult, and therefore valuing them will be too,” says Picagne.

Insurers now have their sights on 2022 as the implementation date for the new accounting rules.

As for the financing of acquisitions, it looks to be the beginning of the end of benign market conditions for debt raising. Will shaky markets break the deal-making wave?

“When asset valuations are very high, M&A looks very interesting,” says Stevenson. “But if you see a big sell-off, whether that’s in asset values, equities, property or debt, does that make it more challenging for people to justify some of these acquisitions?”

Marock disagrees about the impact of market conditions, to the extent that rates are not shooting up. Absent of a financial crash, he thinks this factor will remain on the margin. “I find it hard to believe that a deal that makes sense at 1.5% isn’t going to make sense at 2.5%,” he says. “I don’t think the debt terms are going to make it hard to make deals happen.”

When Derez resigned from the Scor board, the latter said he was “finally facing the consequences of the general conflict of interest situation”. Covéa’s response was equally frosty.

“Despite this continuous attempt to soothe relationships with Scor SE, Covéa acknowledges Scor’s constant refusal to hold any discussion with its largest shareholder, which, from now on, will no longer be represented on the Board of Directors of Scor,” the prospective buyer said in a statement.

M&A tussles can be entertaining to watch. And, as far as the insurance sector is concerned, they are set to remain front and centre of the debt capital markets in 2019.