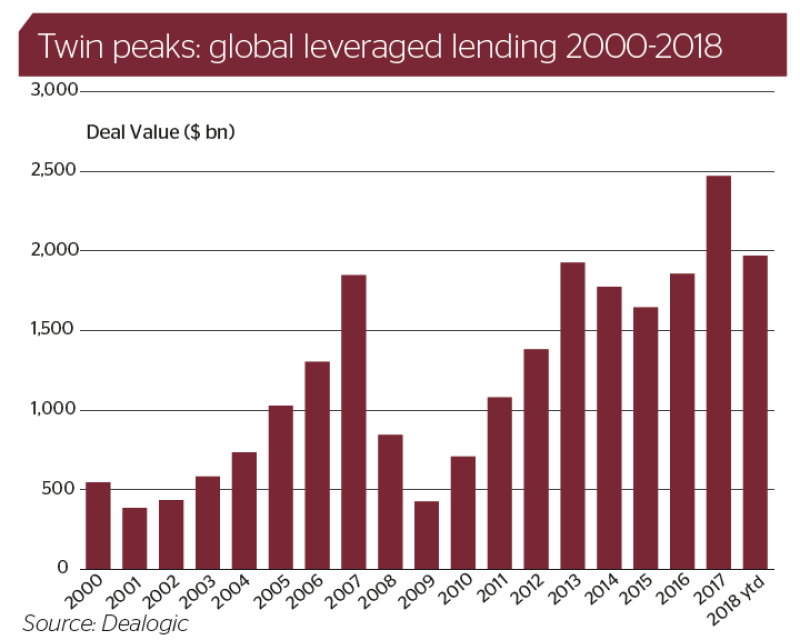

In 2018 regulators and politicians, from Janet Yellen to the Bank of England, turned their attention to a leveraged loan market that many think is overheating. Huge leveraged buy-outs with few investor protections have put some commentators in mind of 2006 and 2007, and some of the market’s biggest names started to pick their spots.

This matters to bank bottom lines. Analysis from UBS and Coalition IndexPlus says Americas DCM is the largest revenue pool in investment banking — ahead of any individual business line in fixed income sales and trading or equities trading.

This is largely down to leveraged finance, and any pull-back in the market hurts revenues. UK banks, by no means the most important players, had an average monthly exposure to leveraged loans originated but not yet sold of around £16bn, or 7.2% of aggregate CET1, according to the Bank of England.

Even if banks manage not to get stuck with “hung bridges” or other risk positions, an absolute drop in deal volume can be crucial for the health of banks’ underwriting business, while investment banks also lend money to loan funds, provide warehouses for CLO issues, and earn a stream of ancillary business from M&A fees to derivatives off the back of leveraged lending.

Vintage year

With the market going gangbusters, 2018 was a vintage year. Dealogic/UBS analysis pegged global leveraged lending net revenues earned by the banks through fees at $13.3bn with a month left to go — down a touch from 2017’s $14.3bn , but well up on 2014, 2015 and 2016.

The market also, until recently, found regulatory favour. The Federal Reserve and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in the US have had longstanding “leveraged lending guidance”, essentially stopping regulated banks underwriting the most aggressive, highly leveraged deals — leaving them to broker-dealers and other non-banks.

But this year the banks were set free. The US general audit office confirmed in late 2017 that the “guidance” should be considered a rule, and therefore required congressional approval, while in February, OCC head Joseph Otting told IMN’s SFIG Vegas conference that the banks were free to do what they want, as long as they had the capital. Under the Obama administration, the agencies enforced a firm line of no deals over six times levered — but regulated banks are now freer to step over this limit.

The European Central Bank published its own guidance in 2017, which was supposed to apply from December. But supervisors have moved softly, and the guidance has had little apparent market impact — deals are still getting done above the six times level which should “raise concerns”.

“There’s an awareness of the ECB guidelines, but it’s hard to be sure it’s had a meaningful impact, whether it’s changing behaviour,” says Paul Mullen, a leveraged finance partner at Hogan Lovell in London. “It’s difficult to determine whether it is regulation or other factors that are driving some banks to limit what they’ll offer. The current guidelines don’t really have any teeth, and it’s not clear they’re being adhered to.”

IMF sounds alarm

By the third quarter, though, tone from the authorities had changed. The IMF’s annual financial stability report warned “The share of highly levered and speculative-grade firms in new debt issuance has grown, fuelled by strong investor demand, looser underwriting standards, and compressed spreads. Notably, highly leveraged deals account for a growing share of new leveraged loan issuance and have surpassed pre-crisis highs. Bank balance sheets have strengthened, but non-bank financial entities have increased their leverage.”

This was followed by interviews from regulators present and past all raising worries about the market, and by the Bank of England presenting a paper comparing the leveraged loan market to US subprime before the crisis. This contained nuggets of comfort, with the Bank pointing out that the market was less reliant on short-term funding than subprime, with less contingent liquidity from the banking system — but with leveraged lending growing 15% a year, according to the paper, it was worth watching.

Some banks have already taken note, at least anecdotally. Morgan Stanley chief financial officer Joanthan Pruzan told investors in the summer: “The market seems a little bit more selective. And good deals are still getting done well, but we have seen some other deals struggle a little bit, not necessarily in our portfolio.”

Steven Siesser, chair of the private equity group at Lowenstein Sandler, says: “I don’t think you can get the same deal done on the same terms as three months ago, there is a little more tightness on pricing, leverage and covenants. But deals are absolutely still getting done. Perhaps there’s a slight bit of the froth coming off the top but lenders, whether the big money-centre banks or the non-banks, are super-active.

“There are some banks out there trying to be a little more cautious, but there’s no shortage of money for sponsors. If someone is bringing in the leverage they’re willing to do by half a turn, the next guy is still doing a turn.”

Deutsche goes for it

In Europe, according to GlobalCapital leveraged finance bookrunner league tables, JP Morgan, Goldman, Barclays and Credit Suisse have all lost ground, slipping one or two places since last year. Meanwhile, Deutsche Bank, Crédit Agricole, UniCredit and Société Générale have all gained ground.

Arranger tables also show stark moves, with Deutsche climbing from sixth in Europe in 2016 to first for 2018 so far. Crédit Agricole and UniCredit have also moved up the table, while JP Morgan has lost some share.

Deutsche said in its third quarter numbers that its levfin market share had climbed from 3.9% to 5% over the past year — partly because 2017 was a particularly tough year for the bank, but also because it’s pressing forward hard, even as it cuts back to become a Europe and Germany focused house.

Dealogic/UBS analysis shows Deutsche making $686m from global leveraged finance fees in 2018, a higher figure than any year since 2014, despite the turmoil in the bank’s C-suite, swinging cuts to fixed income, equities and investment banking, and a full year without bonuses.

“Even if a bank takes a conservative approach overall, that bank may still have a deal they particularly like and be happy to be more aggressive on,” says Mullen. “Perhaps it’s a company or a sponsor they know well or a situation where they’re offering strategic support.

“The fact is, there’s such competition in the market that people are prepared to do things on pretty aggressive terms. It’s about knowing when to draw a line and walk away.”

Non-banks raise their flags

Behind the regulated banks jockeying for position is the huge growth in non-bank involvement in the leveraged finance market. While some regulated banks may be picking their spots and others gaining share, this is dwarfed by the increasing slice of the market taken by non-banks.

Research from Prequin shows more dry powder for private debt in Europe than ever, nearly €60bn in the first half of this year, while last year, 61% of European private debt deals went to funds rather than banks, up from just 19% in 2010.

These funds often target the smaller deals, but behind the syndicated leveraged loan market is a CLO market that’s still going from strength to strength, with $120bn issued year to date, up from $118bn last year. UBS said loan mutual funds, too, grew from around $20bn in 2007 to $170bn last year.

The flow of CLOs, in turn, is anchored by a robust bid from Japanese banks, in particular, for the senior notes which form the majority of the deal size. Unless Japanese government yields spike, these banks are likely to continue forming the foundation of the market — and CLOs are going to continue hoovering up loans as they ramp up.

Debt funds and non-bank lenders also play a crucial role in the more aggressive parts of the market.

“In the more stretched piece, non-bank lenders are continuing to play a very active role. There’s just so much money available chasing deals in the sector,” says Siesser.

Mullen says: “Clearly the banks are concerned about their loss of business to the funds, and some are thinking creatively about ways to protect their market share — for example, formal tie-ups with funds, which allow them to present sponsors a joint solution, or lining up funds as a sell down route before originating.”

Fed fears

Next year, despite the regulatory sabre-rattling, there are few things likely to trip up the market. Recent equity volatility has slowed deals and encouraged some sponsors to postpone their most aggressive issues. Renewed trade wars, slower growth expectations or market disruption could derail the leveraged finance train — just as they could derail other markets.

But the biggest issue for this mainly floating rate market is the expected Fed rate hikes. UBS estimates that there is $3tr of US speculative grade floating rate debt, not just public, syndicated deals but including mid-market and bilateral issues. It expects that CCC-rated borrowers will start to be downgraded if Libor rises between 75bp and 100bp, as this might mean some borrowers struggle to service debts. If the Fed holds off until May the market could keep on trucking all year.

Banks are keen to emphasise that this cycle is different — and, perhaps, for them, they’re right. Even Deutsche, shooting back up the league tables, claims: “We certainly are not increasing our risk appetite… we are doing the underwritings in line with our existing risk appetite… with the expertise we have both on the front office, but, in particular, also on the credit side, we feel absolutely confident,” according to chief executive Christian Sewing on wthe bank’s third quarter call.

But caution from the regulated sector won’t be enough to take the heat out of the market, as funds rush in where investment banks fear to tread.