European companies in the bond markets enjoyed a vintage year in 2017. The European Central Bank’s quantitative easing programme helped drive spreads lower and kept volatility at bay. Almost all issuers benefited, either directly or indirectly, but none more than Italian companies.

Established borrowers issued at tighter spreads and in longer durations. Issuers not seen for several years returned to the market. And first time issuers offered investors extra options for investing in Italy. In fact, 2017 was arguably the year when Italy’s companies finally shook off the taint of the country’s financial woes.

“Italy has been through a difficult time since the beginning of the crisis in 2008 and then the political crisis after the demise of Berlusconi’s government in 2011,” says Gianmarco Viglizzo, managing director in debt capital markets at Crédit Agricole in Milan. “The market has never really been shut for Italian corporates but there has been a time when periphery was a buzzword and Italy raised eyebrows. That has practically gone away now.”

Indeed, Viglizzo goes as far as to say that Italy no longer seems to be a major factor driving investors’ credit decisions. “It all boils down to each issuer’s individual credit story rather than being Italian, currently,” he says.

Giulio Baratta, head of investment grade finance and investment grade bonds at BNP Paribas, puts it slightly differently. “Investors do observe Italian macro fundamentals and credit fundamentals for corporates,” he says. But he adds: “Both have been positive clearly in 2017. Italian large corporates all get ratings better than the state, so they position well compared to the rest of Europe. So far in 2018 we have experienced an extremely constructive market for Italian corporates.”

But what of the rest of 2018? One potential stumbling block is the general election, scheduled for early March. This is one of the top political risk events on European financial markets’ radar screens in 2018.

Polling has consistently shown the populist, eurosceptic Five Star Movement as the most supported party. However, its founder and president, Beppe Grillo, has refused to be associated with any of Italy’s older established political parties.

This could allow a centre right coalition, headed by former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s liberal conservative Forza Italia party and the more right wing regionalist Lega Nord party, to form a government. Financial markets would be likely to see that as a favourable result.

Indeed, there is a consensus among bankers that only if there is a clear victory for one of the populist parties will there be anything more than minor volatility around the time of the election.

Taps are tightening

Meanwhile, market participants are beginning to consider how European Central Bank president Mario Draghi may finally turn off the taps of his bond buying programme.

“We do not see the end of QE changing anything in 2018, but it will have an impact when it happens,” says Carolina Marazzini, head of debt origination Italy at UniCredit. “Not in terms of size [of issuance], but mainly in terms of cost.”

Federica Sartori, director in debt capital markets corporates at BNP Paribas, expects quantitative easing to last until the end of the year and that the corporate element of it, the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme, will remain a big part of it.

“This will allow credit spreads to remain at tight levels,” she says. “We believe there is more rate risk than credit spread risk and we would expect issuers to frontload their funding plan by the summer.”

Baratta thinks there might be a small amount of volatility at the end of CSPP, but does not expect it to be “market-changing”.

However, there is a potential speed bump on the horizon. ECB president Draghi, who was Bank of Italy governor before taking his current job, will hand over to a successor in October 2019.

“At some point the market will have to consider the succession plan beyond Draghi. He has been very supportive of unification and market stability in the periphery of Europe. We have to see if there will be a link between his successor and the periphery. It has not yet been a topic for market participants, but is likely to be discussed in 2019.”

Not the only show in town

Bond market participants everywhere are nervous about what will happen when the vast and unprecedented wave of central bank stimulus since 2009 ebbs. But it would be wrong to think QE was solely responsible for the present debt markets’ very supportive conditions for Italian issuers.

“QE definitely helped, but the picture was looking good before CSPP came along,” Viglizzo points out.

Spreads have been tightening for issuers of all credit qualities quite consistently for the last six years.

“Definitively the ECB has been the largest ‘new’ investor, but we have also seen new investors coming from outside Europe, mainly from the east,” says Marazzini.

“The clear evidence is that the difference from before is that where demand from investors was focused on Italian corporates with large international business, nowadays also corporates with pure domestic activities are frequently included in the investors’ buy lists.”

As spreads tightened and investors found it more difficult to hit their return targets, existing issuers were not able to provide such returns, so conditions were created that allowed new issuers, many of them speculative grade, to issue bonds.

The importance of diversification

One of the pillars of stable access to markets is diversifying the sources of money a company uses to finance itself, increasing the number of investors it can reach. For Italian firms that can mean exploring beyond the euro bond market, on which they are heavily reliant.

“Enel had huge success going back to the Yankee market last year,” says Viglizzo. “Euro investors have acknowledged Italy is making progress, but also now US investors too. Asian investors remain a bit more elusive, but Asia has never been a big investor in Italian bonds — from BTPs down.”

Access to different markets and currencies has more than just a diversification benefit, argues Baratta: “It means issuers can enjoy access to a wider spectrum of financing instruments, so they can be more opportunistic and tap markets when it looks convenient to do so, in terms of tenors and pricing.”

One class of instrument that gives access to different pools of money — and can help to reduce overall financing costs — is green and socially themed bonds. Italian issuers became noticeably busy in this market in 2017.

Enel, the electricity and gas company, kicked the year off for green issuance when it launched its first green bond in January. It was followed by four other issuers. “I sense a growing interest,” says Viglizzo. “A number of issuers were quite sceptical at the beginning when Hera sold the first one in 2014, but in 2017 alone we had four new issuers. That has raised the level of attention and lots of issuers are asking about green bonds today. And at a political level, the level of attention has increased as well. Italian politicians talk much more about sustainable growth and investment.”

Strange reversal

The Italian government itself has been considering a green bond, although the complexity of how funds and budgets are organised at national and regional level could prove a challenge.

Such a deal would be of particular interest because of the unusual relationship in Italy between government and corporate bond yields. Several Italian companies actually trade more tightly than BTPs.

Part of that is due to their own merits. “Italian corporate balance sheets are very sound right now,” says Marazzini. “Most of the refinancing they have done has been with longer tenors and at a lower cost, improving financial efficiency, coupled with increased business profitability. Balance sheets are now ready to use current favourable conditions for opportunities of external growth.”

As Baratta puts it: “The balance sheets of large corporates have been regularly deleveraging, and they have taken advantage of open markets for financing and also asset-liability management exercises involving longer dated issuance.”

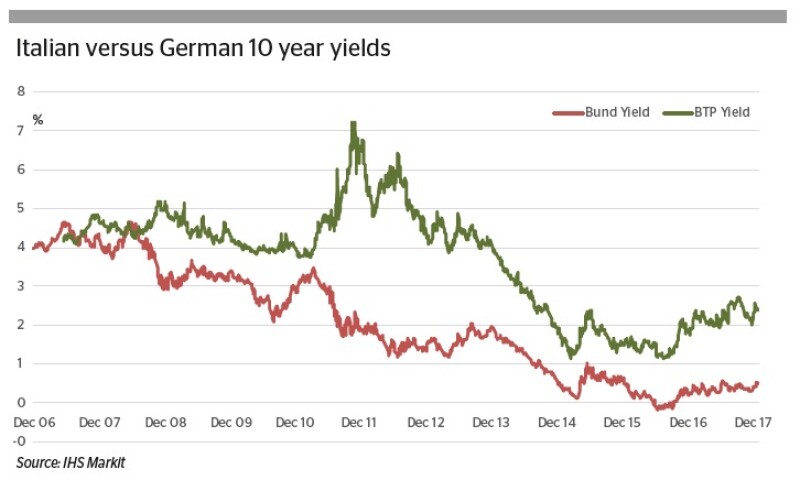

But the peculiar reversal in the normal hierarchy of debt costs mainly came about because the country’s ratings slipped following the financial crisis. In 2006, before the crisis, Italy was rated Aa2/A+/AA-. In 2011 it was put on negative watch, which brought about a series of cuts, and by 2016 it had fallen to Baa2/BBB-/BBB+.

Fitch’s April 2017 cut to BBB was the low water mark, as in October 2017 Standard & Poor’s raised its rating on Italy for the first time for nearly 30 years, putting all the rating agencies on the same mid-triple-B level. This has prompted many to believe that BTPs will now tighten, and that Italian government debt, whether green or not, is a bargain.

“Some investors have started to question corporates trading so far below BTPs,” says Viglizzo. “Italy suffered multiple downgrades and has been slower to recover than Spain, Ireland and other periphery countries. So BTPs have underperformed. Meanwhile, Italian corporates have performed in line with the market and maybe outperformed some of their international peers. But as BTPs recover compared to Bunds and other sovereigns then I would expect the gap will narrow again.”

The decade since the financial crisis has proved that Italy’s large companies can ride out very tough markets.

The political and monetary policy risks of 2018 look like a picnic by comparison. If events turn out badly, the chances are that Italian firms will still be able to finance themselves successfully in a variety of ways.

And if, as expected, the election on March 4 goes the way the financial markets hope, Italian government bonds are likely to continue their improving trading performance. Sooner or later that will take their yields back inside those of the country’s top companies.

But observers expect to see more successful borrowing by Italian companies in the international bond markets in the coming years, irrespective of how fast the sovereign’s standing recovers, or what the ECB does with monetary policy.