First and foremost, bundling up sovereign bonds into a securitization is backwards thinking at the textbook level. One uses securitization to make an illiquid product — say, credit card debt — into a liquid asset. But sovereign bonds are as liquid as it gets — and bundling a Bund with a Lithuanian sovereign bond is hardly going to make the latter more liquid.

Furthermore, the structured product market is far more likely to shut at times of stress than the government bond market. But sovereign issuers need to be able to print at all times — weakening that ability could create far larger problems than the one this solution claims to sort out.

There are also serious questions over how the securities would be structured. Should they link weightings to GDP? What happens then if relative GDPs change?

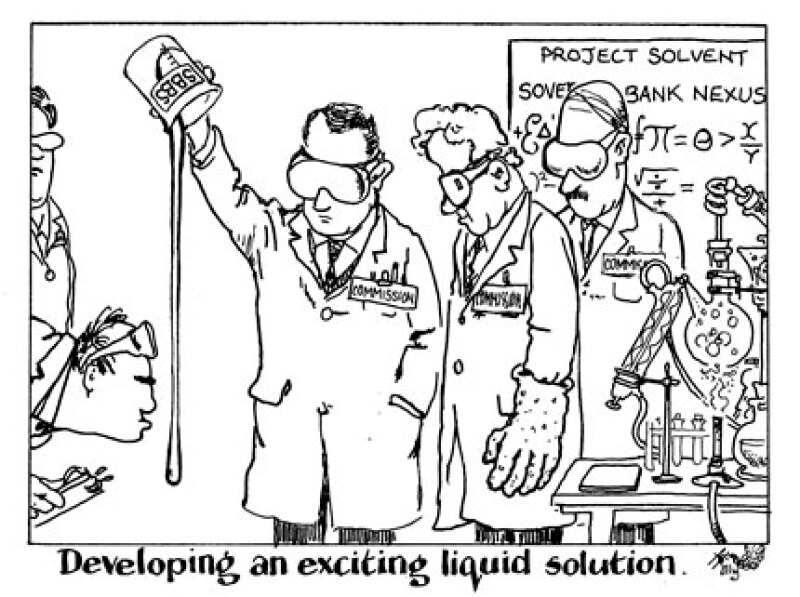

If the Commission really wants to break the link between banks and their sovereigns, it needs to either create true debt mutualisation — politically unlikely, especially given the results of last month’s German election — or force banks to diversify using laws or obligations.

Both those solutions are fraught with difficulties and their own problems. But if the Commission is serious, far better it look to those than creating a product that none of its sovereign issuers — who are surely among those most keen for a safer eurozone bond market — either wants or needs.