When the European Commission first proposed in 2010 that bank bail-ins — the mechanisms designed to help a failing bank absorb losses and recapitalise itself — should include senior unsecured bonds, it sent a shockwaves around the FIG market.

Following the financial crisis everyone had been clear that banks would have to build up strong layers of subordinated debt, to absorb losses and allow a bank to fail without going into formal bankruptcy procedures.

But senior bondholders had always assumed a different role. There were big legal barriers stopping them from facing losses outside of liquidation, and there had always been the implicit assumption that the state could step in and help them out.

Fast-forward seven years and those assumptions have gone. Senior bank debt investors have quickly grown used to the idea that their financial interests are linked to the health of the issuer and, with interest rates at all-time lows, they have been happy to collect better returns for accepting a new level of risk.

But placing senior bondholders on the hook for losses has to some extent made it difficult to distinguish between the role of regulatory capital and the role of other loss-absorbing instruments.

“As you get a build-up of bail-inable senior bonds it will be interesting to see how the product interacts with tier two,” says Barry Donlon, global head of capital and liquidity solutions at UBS in London.

European banks have already started pumping the capital markets full of loss-absorbing senior bonds as they work to refashion their debt structures to comply with global and regional capital standards — the Financial Stability Board’s total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) demands and Europe’s minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL). But market participants have yet to agree on where these new forms of debt should be priced.

By various estimates, bail-inable senior bonds trade about 40bp tighter than their tier two counterparts, and are about 30bp more expensive for issuers than traditional senior unsecured debt. Many FIG bankers argue that the securities should become even cheaper for issuers as the market matures.

That’s partly because senior bonds will only absorb losses during a resolution, while regulatory capital will absorb losses when a bank starts to fall below its minimum capital requirements, at the point of non-viability (PONV). And if a bank hits its PONV and is placed in resolution at the same time, Sandeep Agarwal, co-head of the capital market solutions group and head of EMEA DCM at Credit Suisse in London, says that senior bondholders are still far less likely to take a hit than tier two or additional tier one (AT1) investors.

Based on the average capital strength of European financial institutions, an issuer would probably have to burn through half its common equity and lose subordinated bonds worth 4%-5% of its risk-weighted assets before regulators even had to think about imposing losses on more senior parts of the capital structure.

“It makes no sense that tier two and non-preferred senior should trade closely together,” says Credit Suisse’s Argawal. “We are already starting to see this dynamic play out in the differential between TLAC bonds and preferred senior bonds.”

Subordination state

Discrepancies have also emerged in the way that different types of bail-inable senior bonds trade in the secondary market.

Some FIG bankers have noted that non-preferred senior instruments have been quoted slightly wider than similarly rated senior bonds that have been issued at holding company level.

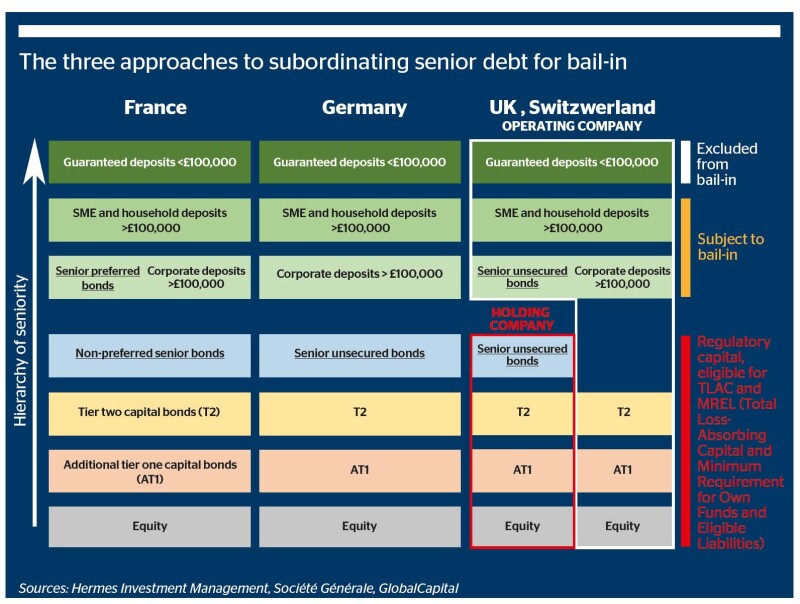

The two forms of debt represent different approaches to making sure senior bonds meet a “subordination requirement” for global capital standards.

UK and Swiss financial institutions have made it easier to bail in their bonds by shifting them on to a holding company that has no operating liabilities, while French banks have recently started issuing what they call non-preferred senior bonds, which is a new asset class ranking in insolvency between tier two and ordinary senior unsecured securities. The two types of instrument carry similar risks for investors, and should trade in line with one another.

Part of the problem is that some index providers have put non-preferred senior bonds into their subordinated bond indices, while holding company level senior bonds have remained in the traditional senior indices.

When an investor is trying to replicate an index, such a framework does not incentivise investment in non-preferred bonds, as those instruments are likely to have far lower spreads than the majority of other deals in the same index.

Forward lurch

But even as the market for loss-absorbing senior bonds matures and moves towards a consensus on pricing, issuance volumes have surged.

“The MREL and TLAC space has produced different solutions for banks jurisdictionally and investors have got to terms with these differences and have shown very strong appetite for the products on offer,” says Mark Geller, deputy head of FIG DCM for EMEA at Barclays in London.

“This has led to the recent swift development of the non-preferred senior market. Given the securities sit towards the top of the capital structure and because ratings have tended to be investment grade, it has been easier for investors to consider fund mandates and the risks involved.”

Since Crédit Agricole opened books on the first non-preferred senior offering in December 2016, French global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and Santander have managed to issue about €20bn in the format. According to research from BNP Paribas, these banks still have about €12.8bn of non-preferred senior issuance left to do this year.

Indeed, the non-preferred senior bond market has the greatest room to develop over the coming years, given that a large proportion of the European banks that have holding companies have been using the structures to issue MREL and TLAC debt for several years now.

Many member states are first waiting for European authorities to agree on a set of European rules that would harmonise insolvency law by establishing non-preferred senior bonds as a new asset class.

In February the Swedish National Debt Office (SNDO), for example, said it would encourage firms to start issuing non-preferred senior bonds once Europe has set out its final changes to bank creditor hierarchies. Issuing the new type of debt before insolvency laws have been updated would be difficult, as many outstanding tier twos contain covenants blocking further subordination. Sweden’s four largest banks will have to issue up to €53bn of eligible bonds over the next five years to comply with MREL. Nordea is the country’s only G-SIB, and accounts for about €15bn-€20bn of that requirement.

“Because the framework for non-preferred senior is not yet in place in most European jurisdictions, some banks have run their tier two buffers higher than they might have otherwise done,” says Peter Jurdjevic, head of global financial solutions at Barclays in London.

“Once insolvency regimes are modified, we may see a recalibration of those banks’ capital structures to reflect a larger proportion of senior non-preferred instruments for bail-in purposes.”

Fortunately for the banking sector, the switch to issuing non-preferred senior bonds will not lead to a huge increase in overall net supply year on year.

Most financial institutions should be able to meet their TLAC and MREL requirements simply by refinancing old senior unsecured instruments with new types of loss-absorbing debt.

BBVA has even said that it expects its MREL issuance needs could be lower than its wholesale funding maturities in the coming years. But by the time non-preferred debt market has been rolled out across Europe, bank senior bonds will have witnessed a fundamental sea change.

Where once the word “senior” meant very clearly that creditors ranked pari passu with the operational liabilities of an issuer, from 2017 onwards the asset class will come to resemble a privileged form of subordinated debt.