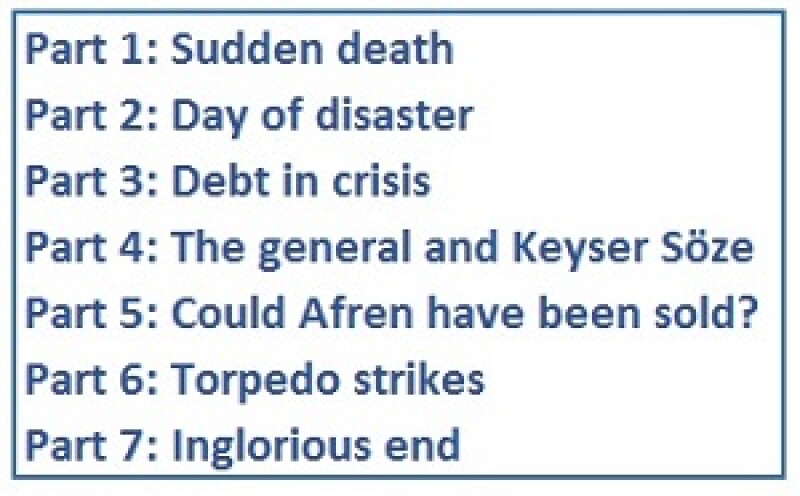

[Part 2: Day of disaster] | [Back to main page]

On March 13, the firm announced a plan to secure interim funding followed by a refinancing.

Afren had reached a conditional agreement with noteholders holding 42% of the outstanding principal of its three bonds. They would provide $200m of net interim funding as a super-senior private placement, by the end of March 2015.

The noteholders providing this funding were called the “ad hoc committee” and included, according to a restructuring source, investment funds Pimco and Ashmore as well as, with smaller positions, Halcyon and GLG.

The private placement was to be repaid out of an issue of $321m of new high yield notes, which would provide an additional $100m of net cash to the group. The notes were to be issued in mid-July, as it was clear from the start that Afren might run out of money then.

The three outstanding bonds totalling $863m, meanwhile, would be replaced by two $350m bonds due in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

A debt-for-equity swap would also give bondholders about 89% of Afren’s share capital, with existing shareholders diluted to 11%.

For its restructuring, Afren thought big. The firm provisioned $48m to pay its own legal counsel and advisers, as well as its creditors’ legal counsel and advisers, including Blackstone. That sum was also to cover due diligence done around the restructuring, and the fee for registering Afren’s new debt with Nigerian authorities. That last item was the most expensive component of all by a long margin, according to one adviser.

Much of the $48m was to come from the refinancing itself, as Afren could not spare that kind of money.

Alvarez & Marsal, the firm that had managed Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy estate and assets, was among the firms hired by Afren to work on the restructuring, as was Morgan Stanley. Morgan Stanley’s head of European restructuring, Ben Babcock, masterminded the deal, two sources said. Babcock had completed every restructuring he had ever led, they added.

Creditors at loggerheads

But if Afren had thought the plan would go smoothly, it was in for a surprise.

Access Bank and Zenith Bank, two Nigerian banks that had lent bilaterally to Afren, refused to accept the terms of the restructuring.

Afren and most of its lenders had agreed that the bondholders putting in new money would get a senior claim on Afren’s assets, ranking above existing lenders.

As GlobalCapital reported on May 7, Access and Zenith would not tolerate that. Confidential messages seen by this paper showed a long stand-off between the Nigerian banks on one hand, and Afren and its international creditors on the other.

On March 25, a group of nine lenders to Afren — including Bank of America Merrill Lynch, BNP Paribas, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank — wrote to Access and Zenith that there was “no more time”.

Afren was running out of money, and unless the Nigerian banks agreed to the restructuring deal that was on the table, it would go bust.

In that message, the nine lenders hinted to the Nigerian banks that their attitude could affect their future relationships with the international banks — though the nine toned that down in the final version of the letter.

Negotiations lasted another month, in cash-starved conditions for Afren. The group even told its creditors it was no longer able to pay suppliers.

On April 30 — with Afren just “hours from insolvency”, according to three sources — the deal was finally signed. But the Nigerian banks had won — the bondholders had to agree to most of their conditions.

That decision may prove to have a fateful influence on the battle for recoveries from Afren that still lies ahead.

Shareholders revolt

In parallel with this struggle, and unaware of the creditors’ dispute, shareholders started planning a revolt. Some retail investors felt cheated by the heavy dilution proposed as part of the restructuring, and quickly joined forces as the Afren Shareholder Opposition Group.

Asog, which came to be led by four private investors — Tony Harding, Ainsley Smith, Fraser Stock and Peter Brailey — grew over time.

Brailey, its spokesperson, said Asog would fight for a deal that was both more viable for Afren and less damaging to shareholders. He told GlobalCapital: “We see an unfair situation and we don’t want to put up with that. We’re prepared to stand up and be counted.”

Afren’s AGM was scheduled for June 25. Shareholders did not have the right to vote directly on the restructuring itself, but their approval was needed for the dilution part of the deal, and that was to be sought at an extraordinary general meeting, to be held in late June.

In Asog’s view, the new funding was insufficient, and the dilution too heavy. It planned to vote against the restructuring at the EGM.

At first, Afren, its creditors and advisers were unsure how to deal with the threat. Some thought Asog presented no real danger to the restructuring; others were worried. The shareholders were vocal, debating the situation on an online forum and social media. Creditors and lawyers spent time reading their internet posts, trying to assess the nature of their claims, according to two sources who worked on the restructuring. But no one knew how many votes they would be able to muster.

If the shareholders voted in favour, the restructuring would go ahead and bondholders would assume control of 89% of Afren’s stock, with a further $75m capital increase to come.

If the shareholders voted against it, the restructuring would still take place. Instead of getting new shares in Afren, the bondholders would be able to appoint a majority of its board and conduct by the end of 2016 a sale of some or all its assets — either to third parties or to themselves.

A No vote would have endangered Afren’s very existence, and the creditors were desperate to avoid it.

A source close to Afren said in mid-May that Asog was a small group fighting the wrong fight. And Afren publicly said many times that a Yes vote was the only way for shareholders to make any return on their investments, in spite of the dilution.

Shareholder threat grows

But behind the rhetoric, Afren was starting to take Asog, an obstinate if amorphous group, more seriously.

Alan Linn, who was announced on April 30 as Afren’s new CEO, replacing Toby Hayward, met representatives of Asog within days of his appointment. He said he would facilitate a meeting between Asog and the bondholders.

Linn, a veteran of the oil and gas industry and a chemical engineer by training, was popular with shareholders. They saw him as fresh blood, much needed in a business that had tanked under previous management, and respected his experience at companies including Exxon, Cairn Energy and Roc Oil.

On May 20, Asog told Afren that it represented 10% of the group’s share capital — more than any single shareholder. The claim was difficult to verify but, if true, would have made it a powerful force at the EGM.

Having long put off meeting Asog, the bondholders, through their adviser Blackstone, finally agreed to see the group. They met at the London office of Morgan Stanley, a restructuring adviser to Afren, on June 10.

During the meeting, which one participant described as “courteous but robust”, Morgan Stanley’s Ben Babcock effectively acted as moderator between Blackstone’s Martin Gudgeon and Asog’s representatives Harding and Brailey. Both sides expressed their views and yielded little. Asog never met Blackstone again.

[Part 4: The general and Keyser Söze] | [Back to main page]

.

Unless otherwise stated in this article, none of the individuals and institutions mentioned agreed to comment on the record.