The state-owned company is looking for $100m-equivalent borrowing in euros, along with an additional $150m-equivalent through a greenshoe option.

Its latest request follows an attempt at a fundraising in 2016 that market sources said was scrapped because of mandatory hedging requirements.

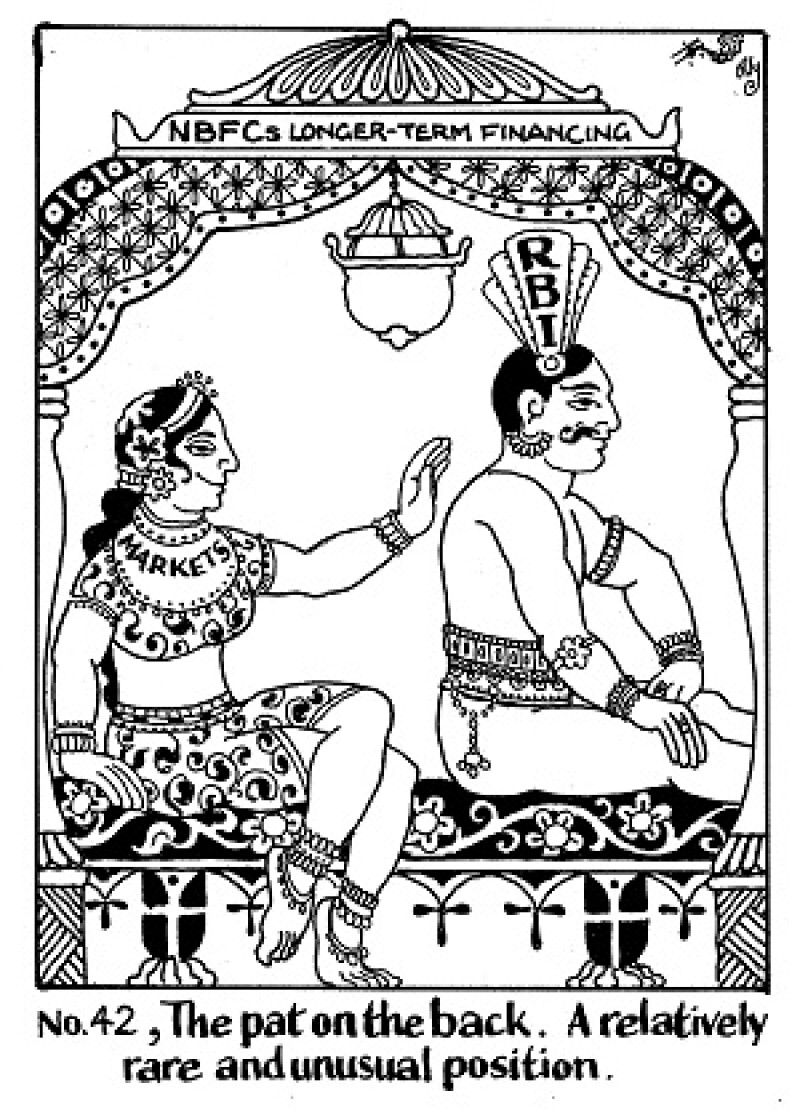

The RBI has a labyrinthine set of rules governing offshore financing. The relevant one in this situation is that non-bank financial companies (NBFCs), infrastructure firms and those that support them are eligible to raise minimum five year foreign currency loans but on the condition that they are fully hedged.

The additional cost of hedging diluted the benefit of raising a dollar-denominated loan to such an extent that it made more sense for PFC to stick to local options, sources said at the time.

This time around, it has approached banks under track II of the Reserve Bank of India's guidelines on external debt, which allows NBFCs and infrastructure firms to issue debt with a minimum maturity of 10 years, most importantly with no mandatory hedging. However, Indian banks are not allowed to provide any of the funds.

Asset-liability mismatch

But now that a request for proposals has been issued, several banks that GlobalCapital Asia spoke to were open to the idea.

After all, PFC finances power projects and often borrows for the purpose of lending on. Because infrastructure projects typically take a longer than the conservative five year bank loan time-frame to become viable and generate steady cashflows, a lot of PFC’s previous, shorter tenor financings would inevitably end up getting refinanced for another three to five years.

To minimise asset-liability mismatches, longer-dated debt makes more sense. In this case, the amount PFC is seeking is not particularly large and because it is looking for euros, bankers reckon it should be able to get funds at very competitive pricing, notwithstanding the tenor.

Though the loan has a bullet repayment, on an average basis, PFC will have to set aside a smaller amount to service the loan because of the longer time period than it would in case of shorter-dated debt. This will help it smooth out cash flows.

Of course lenders will no longer have the option of exiting after five years, or repricing the deal according to prevalent market conditions. But in a market environment where there is plenty of liquidity and relatively few high grade options to put money to work, banks are learning to adapt their requirements, be it on tenors, pricing or even covenants.

The initial resistance was understandable, especially as the RBI does not have the best track record when it comes to introducing regulations for overseas debt. But by making 10 year debt a more cost effective funding option than five years, the central bank has created a market for longer-dated bank loans to Indian companies.

And while it will take a few strong names like PFC to open up and establish the framework, once banks start becoming more comfortable with the idea, private companies could follow suit. Talk about hedging your bets.