India’s equity capital markets are on track for their best year since 2011 and they owe it to the booming IPO market. Other types of capital raising have punctuated the year – a block trade here and a qualified institutional placement there – but listings are what drove the year’s strong performance.

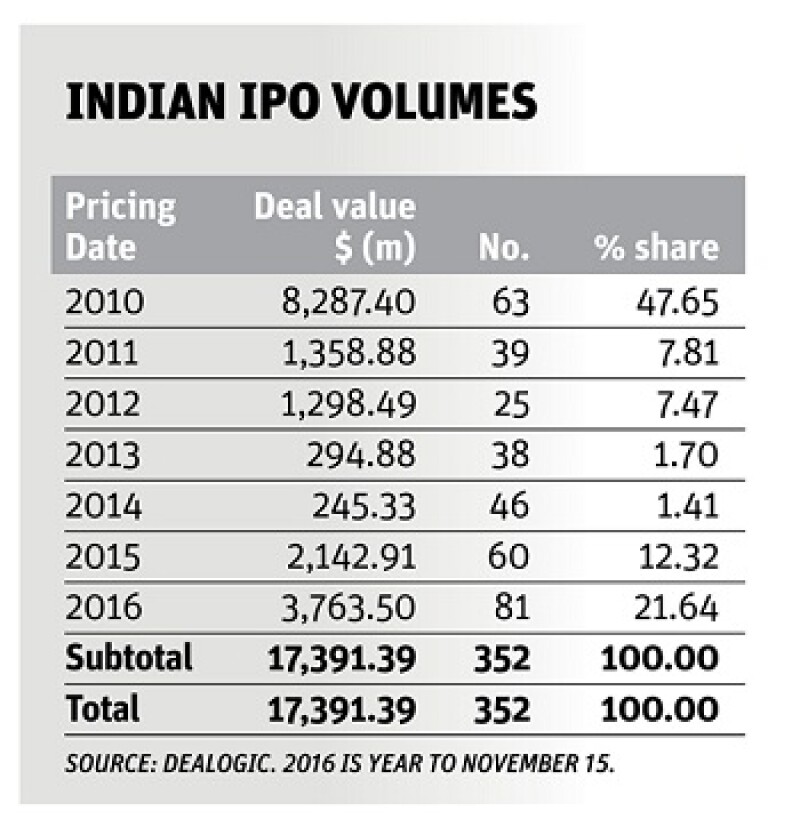

IPO volumes and the number of deals were at a six year high by mid-November. There were $3.8bn worth of share listings and 81 deals, compared to just $2.15bn and 60 throughout the whole of 2015, according to Dealogic data.

A number of key factors drove the jump this year. On the domestic front, there has been a shift away from hard assets such as real estate and a preference for higher returns. As a result, inflows into domestic mutual funds have been growing, which has bolstered demand for equities. And while funds snapped up shares in the secondary market, demand ultimately overflowed and became a driving force in primary activity, say bankers.

“Mutual fund plans are attracting inflows, as much as $300m-$400m every month, so there is pent up demand for paper,” said Samarth Jagnani, executive director and head of capital markets India at Morgan Stanley. “And there is only so much to buy in the secondary market, so the demand has flown into the primary market.”

The shift came as real estate and other assets, such as gold, lost their shine. Oversupply in the real estate market pushed buy and hold investors or those buying as a capital asset or investment opportunity to move their money elsewhere.

Meanwhile, gold has been in a trough. After a boom in the value of gold following the financial crisis, it has suffered since then. There was an upswing in the returns of gold funds in 2016’s third and fourth quarters, but the confidence in the stock markets and desire for greater returns means equities have become more sought after.

And, India’s equity markets have offered a compelling investment story.

“India is not considered the same as other emerging markets, where you might make 20% returns but take on a large amount of risk,” said a senior equity markets banker in India. “India is more stable now, returns might be around 10% or less but it is a safer investment.”

Macro shift

India’s booming equity market is also a reflection of the country’s positive macro picture. The economy as a whole is on the up, with the World Bank forecasting GDP growth of 7.68% for 2017 – the fastest growth of any country in Asia. And after two years in charge, prime minister Narendra Modi has delivered an impressive turnaround from the paralysis left by the previous leader Manmohan Singh. And this year businesses started to tap the markets to realise their growth aspirations.

“Companies are showing more interest in capital, in growth, so they are investing in capital expenditure,” says Manan Lahoty, a partner at Indian law firm Luthra & Luthra. “Sentiment has been like this since [Modi] was elected in 2014, but it has taken a couple of years for people to utilise capacity and to look to expand. Now we are in the expansion phase.”

The Modi government made a handful of moves that got markets excited, the most headline grabbing of which was a surprise decision in November to replace the Rp500 and Rp2000 ($29) notes in a bid to combat corruption.

And in August, Modi enacted the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which will create a common market across the country, which until now has been weighed down by a complex array of different tax systems for every state.

The announcement of the GST boosted sentiment because it showed the government means business, say observers – particularly as Modi has declared he will keep to a deadline of April 1, 2017 for implementing the tax. Foreign investors certainly took notice.

“Flows into India from foreign institutional investors have been growing but in the secondary market there is only so much to buy leading to demand for new paper,” said Jagnani. “If new stocks perform well then that demand increases and in the climate at this moment new paper is doing well.

“As a result, the primary issuance pipeline and FII inflows will continue to exhibit a positive trend.”

Rich with diversity

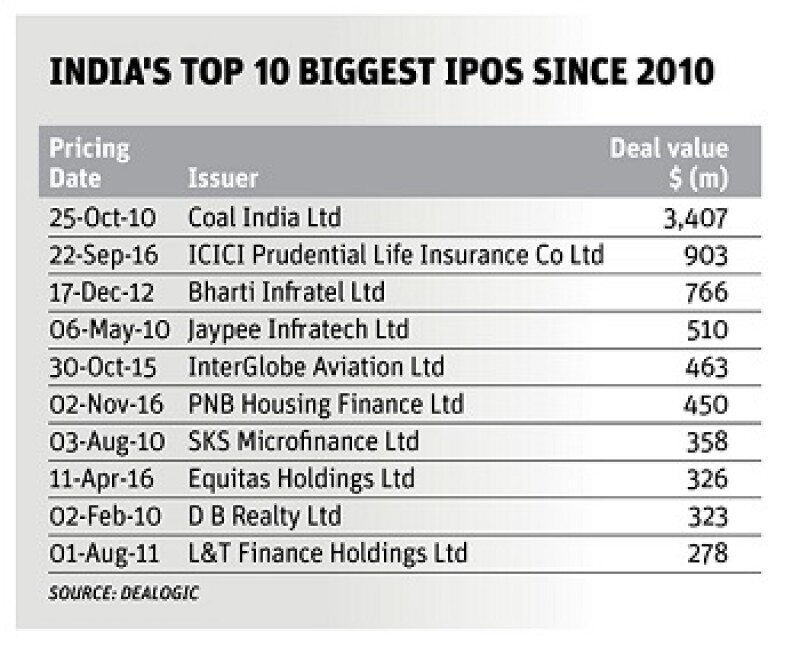

The positive backdrop invigorated India’s IPO market, bringing with it a breadth of opportunities from rarely seen sectors. For example, in August RBL Bank brought the first IPO from a bank in over 10 years while cancer and fertility care provider, HealthCare Global Enterprises, raised Rp6.5bn in March. Arguably the most headline grabbing deal came from ICICI Prudential Life Insurance Co – the country’s first ever listing from the insurance sector and the largest IPO in six years.

ICICI Prudential floated in September for Rp60.6bn, the largest IPO since Coal India listed for $3.4bn in October 2010, according to Dealogic data. The success of the life insurance sector’s outing in the market has participants excited about seeing more from the industry. Potential candidates include SBI Life Insurance Co. And more activity is needed for the sector to gain some real momentum, says Luthra & Luthra’s Lahoty.

“Once a couple of transactions go through then there will be more IPOs which will help encourage even more,” he says. “I’m not entirely sure how quickly insurance companies will tap the markets. But we will see them in the headlines because they offer a new product, a new sector.”

ICICI Pru was not initially flagged as the sector’s trailblazer, that was HDFC Standard Life Insurance Co which had approval from its board of directors and had hired a team to run an IPO. But it decided to opt for a backdoor listing by merging with Max Life Insurance Co which in turn had merged with its listed parent Max Financial Services.

Investment trust debut

And in 2017, India’s equity market will get a further boost with the introduction of investment trusts. Infrastructure investment trusts (InvITs) are most likely to be first and real estate investment trusts (Reits) close behind.

Over the past few years there has been a lot of noise in India about InvITs, mostly from the government as it tried to kick-start the asset class. Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) first finalised the regulations in September 2014. It published a consultation paper on the regulations in August 2015, which it followed up with a second in December that year.

“Reits and InvITs have taken a while to develop, but they are good because they offer a fresh avenue to invest,” said Pranjal Srivastava, head of equity capital markets at ICICI Securities, adding that “the first few will need to be attractive to build that market”.

The government has been pushing the product and is working to clear up any issues with the rules and regulations.

“India has benefited with the proactive action from government and other regulatory agencies,” said Srivastava. “Sebi heard us out – they are being proactive on InvITs and Reits. They are doing what they can do on this.”

IRB InvIT Fund, sponsored by IRB Infrastructure Developers, is on track to christen the asset class, having filed its draft IPO prospectus in early September. The listing will include an issue of primary shares worth up to Rp43bn, according to the document. It will also have an offer-for-sale of secondary units, the size of which is undisclosed.

Secondary sell-downs

Offer-for-sales (OFS) – which offer a shorter and less complex way for promotors to dilute their stake – were particularly common this year. ICICI Prudential for example was made up entirely of shares provided by its parent ICICI Bank. One reason for their popularity in 2016 is that India is at the peak of an investment cycle, says Sumit Jalan, co-head of investment banking & capital markets in India for Credit Suisse.

“The investment cycle [of private equity] is around five years,” he said “In 2011, private equity firms made investments in new companies, and many of these companies have now reached the point where they are ready to go public.”

“As private equity firms cash out from these investments, the investment cycle will start again. I see the cycle starting again around the end of next year.”

As OFS deals create no new capital, some media coverage has put them in a negative light. But really it can be a way to avoid bloating companies with something they don’t need, says Srivastava.

“In the majority of IPOs the company’s private equity investors are exiting either partially or fully,” he says. “But these are very healthy companies so they still attract investors. And it is good for them not to raise capital they don’t need.”

Regardless, secondary share sales are a mainstay of a market like India’s, says Anand Gupta, portfolio manager at Eastspring Investments. “In such a vibrant market you will have issuance where private equity firms are just looking to take profit.”

But there is still huge potential for more deals through both OFS and primary deals given that so much of the market is still in the hands of families.

“Family promoters still own more than 47% of the market in India,” says Gupta. “The market capitalisation to GDP ratio in India still has long way to go, it is very low. So it is prime to pick up and will only pick up further.”

Over the next 12 months, financial firms and companies from a broad selection of industries will be busy going public, such as insurance, telecommunications, consumer products and services, and healthcare, according to research from Baker & McKenzie. It reckons there are a further 16 companies in the pipeline to list with the potential to raise as much as $5.86bn

Highly anticipated IPOs include those from Vodafone India, which is expected to be around $3bn in size, and SBI Life Insurance Co, meaning there will be plenty to attract investors in 2017.

“India is the most diversified emerging market,” said Gupta. “No one sector has disproportionate weighting in the MSCI India Index. China has SOEs or tech stocks, but India has 16% IT, 21% banks, 10% pharmaceuticals for example. It is a unique universe to play in.

“Investors that want pro-growth stocks, pharma or health stocks or many others then they can get them in India. You can’t get that diversity in most other emerging markets.”

| QIPS: Down but not out The qualified institutional placement (QIP), one of India’s less common capital raising tools, had a tough year, but started to regain momentum at the end of the 2016. QIPs are used by listed companies to raise capital, typically through the issue of fresh equity. The format does not require any pre-deal filings to the market regulator. QIP business had almost entirely dropped off by September, driving the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) to call on local and international banks for advice on how to keep the market alive. Sebi met with banks in August, when there had been just Rp5.6bn ($82.2m) worth of QIPs from four deals in the 2016/17 financial year, compared to 20 QIPs worth a combined Rp193.6bn in 2015/16. The action from the regulator was a positive sign to the market, but there was nothing it could do about the low number of QIPs, which was just a reflection of the market and economic situation. The answer from the bankers was simple: “It is because people and companies don’t need the money. There is not much capital expenditure at the moment and so companies don’t have the need to raise capital,” one banker told Asiamoney. Then in early September, Yes Bank attempted a Rp66bn QIP. The deal was highly anticipated, but after it opened the bank’s stock price plunged and the issuer had to pull out for various reasons not made public. Sources close to the situation say the QIP was hamstrung by a lack of demand and double-counting of orders. Despite the fear of potential trauma following Yes Bank’s flop, a handful of QIPs were successfully completed soon after. The deals that came after Yes Bank, such as Motherson Sumi Systems’ Rp20bn QIP, were a positive sign for the asset class says Manan Lahoty, a partner at Indian law firm Luthra & Luthra. And he expects more as companies head into a period of expansion. “It seems QIPs have returned. There is sustained interest and lots of issuers are looking for this window to open. The QIP market is back it is just a bit late,” he said. |